“THE WINTER’S TALE” COMES TO MINI-FEST

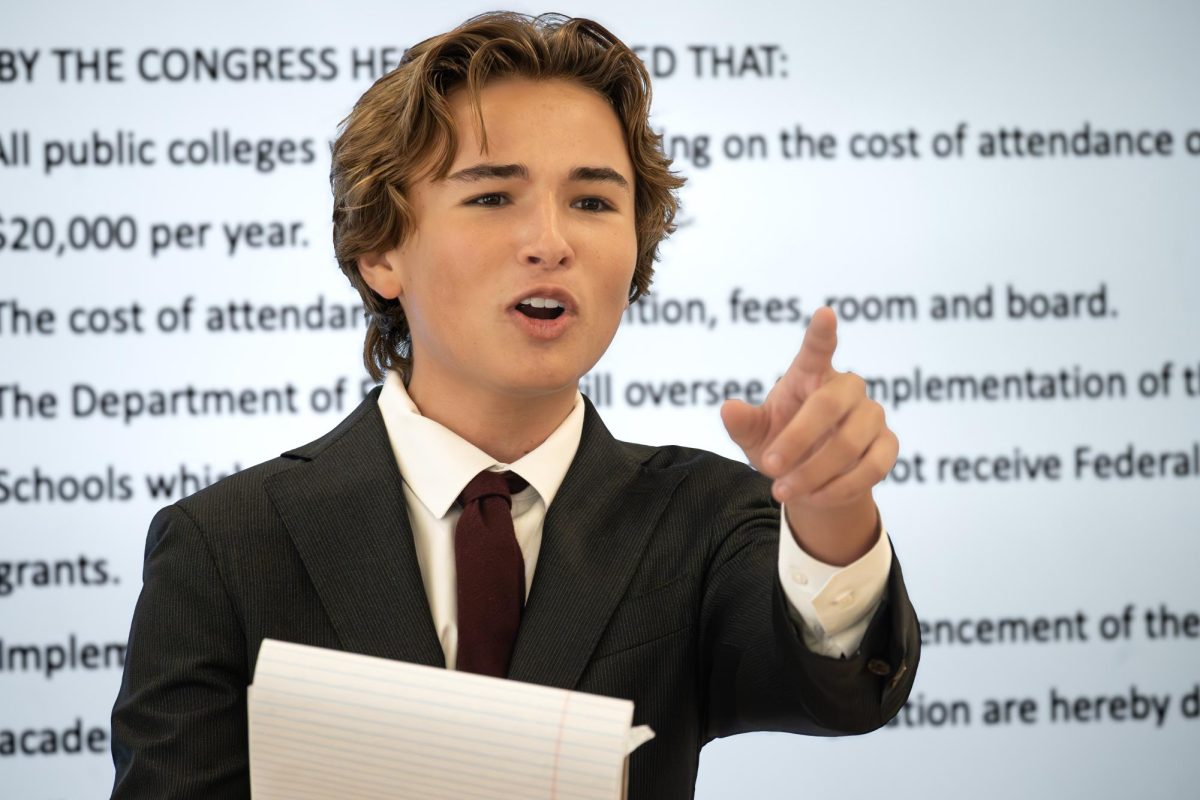

Theatre juniors Alexa Rubenstein and Nathan Gomes played husband and wife in “The Winter’s Tale.” Rubenstein’s character Paulina begins the first act trying to defend her friend, Queen Hermione of Sicilia, against Leontes’s false accusation of adultery. “She’s really empathetic, especially toward women, because she recognizes the injustices at this time,” Rubnstein said. “She’s very strong and fights for what she believes in, which is really admirable because in this time, not a lot of people did that.”

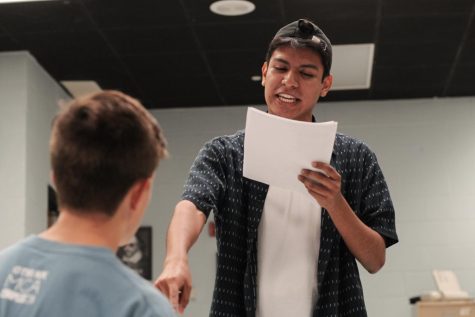

Room 7-110 may as well be the interior of a grand palace hall as theatre junior Jason Roblero directs fellow theatre juniors Nathan Gomes, Seth Greenberg, and Alexa Rubenstein in an excerpt of Shakespeare’s “The Winter’s Tale.”

“‘I am none, by this good light,’” Gomes says to Roblero, who is standing in for Greenberg’s prideful King Leontes. (In contemporary words: “I am not a traitor.”)

A vicious, backhanded slap echoes as Gomes hits the ground.

A beat. Gomes holds a hand to his cheek as if he has actually been hit. Rubenstein rushes to his side. Then, cut.

“Again, again, again,” Roblero says, returning to himself. “Great job on the fall, though.”

This pattern repeats 19 more times before rehearsal ends at 5:30 p.m., and Roblero’s actors take the late train home. The long nights, the tedious repetition, and the impassioned analyses of a centuries-old scene are for a single purpose: success at Mini-Fest, a schoolwide contest that determines which ITS individual events will compete at the district level.

Roblero, Gomes, Greenberg, and Rubenstein prepared the piece as an entry in the festival’s directing category. Roblero, making his directing debut with this scene, took inspiration from English teacher Theresa Beermann, who introduced him to Shakespeare through “Macbeth” in class.

“At first, I really hated [Shakespeare],” Roblero said. “I genuinely did … Then, I had Ms. Beermann. I started to realize that there’s more to this text than people think, that this text wasn’t meant to be read; it was meant to be performed.”

“The Winter’s Tale,” first performed on May 11, 1611, is fundamentally different from Shakespeare’s other works. It begins as a tragedy, a king’s jealousy tearing his family and friends apart, but it ends as a comedy.

“[King Leontes is] definitely guided by pride and this sense of ignorance,” Greenberg said. “He thinks, ‘Oh, my perspective is the only one that can be correct.’”

Their scene, which appears in the first act, has conflict on every front. Rubenstein’s character, Pauline, is trying to convince Leontes to claim the child he fathered outside of his marriage. Leontes wants nothing more than to get rid of the baby. Camillo, played by Gomes, is caught between defending Pauline, his wife, and appeasing Leontes.

“[Camillo is] overprotective,” Gomes said, “and he’s also super frantic and worried the whole scene. […] I think about a real life situation and trying to please two different people. That definitely creates tension.”

To Roblero, his task as director was not to present his actors with his own conclusions about the material; instead, he wanted them to “feel the words.”

“A director’s job is to make the actor realize that they already know the answer to the question that they have,” Roblero said. “I leave a trail for them. You can’t tell them the answer directly because then they won’t understand it for themselves.”

The open-ended script challenged Greenberg to study Leontes’ intentions and emotions in every line.

“If you don’t have the energy to really zone in on what you’re saying, you could lose everything,” Greenberg said. “You could lose the meaning behind your words because it’s basically gibberish. But, it’s well-written gibberish.”

Despite the occasional antiquated phrase, each group member stressed the relevance of Shakespeare to modern life.

“Shakespeare wrote about a lot of pretty common issues,” Rubenstein said. “It’s obviously a different time period, but a lot of the themes are similar, [like] injustice. […] In this scene, I’m a woman who’s lower than [Leontes]. I’m fighting for his wife who we thought cheated on him. He could kill me at any point, yet I’m still fighting.”

Roblero and his actors will perform in the coming week. If chosen for districts, they will bring their scene to an off-campus competition on Nov. 23.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Dreyfoos School of the Arts. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.