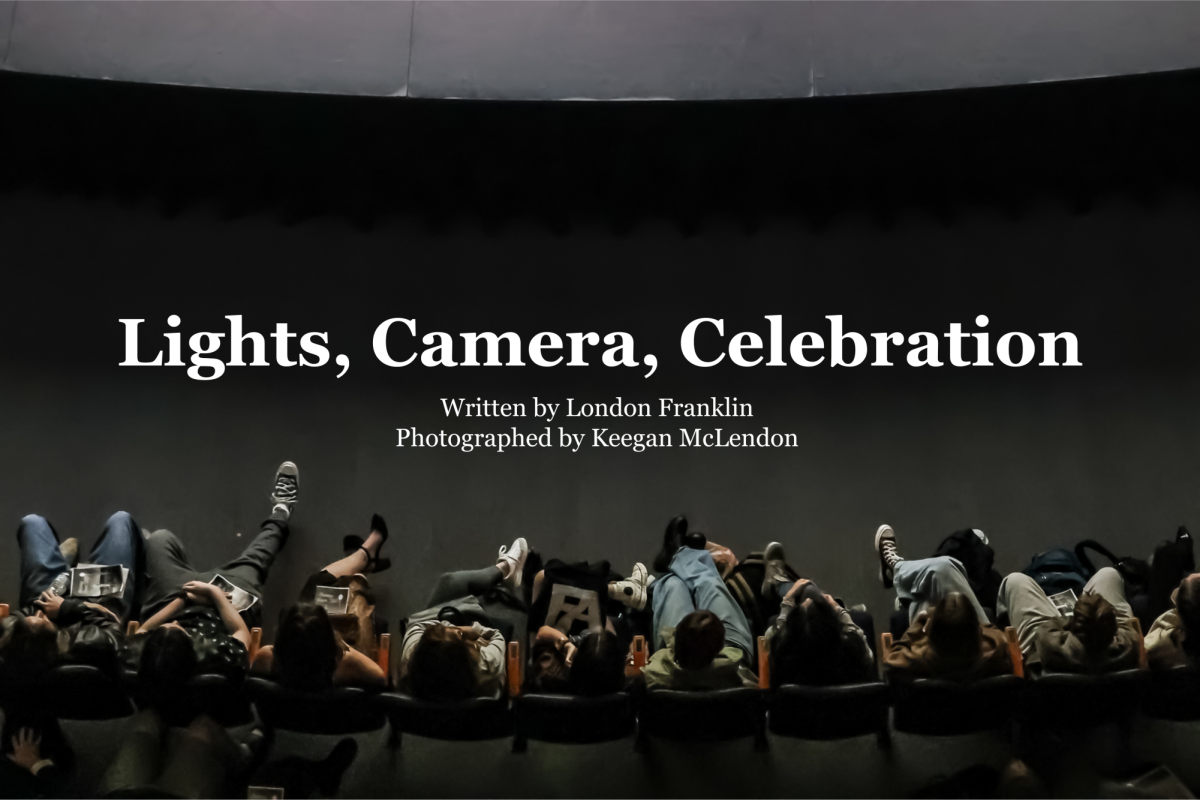

The oldest music has inhabited countless halls and touched more ears than perhaps the loudest voices. On Thursday, Jan. 30, songs from as far back as the 18th century reached the Brandt Black Box Theatre for the piano department’s first concert of the quarter, “Evolution.”

Piano juniors Jason Ibalarrosa, David Liu, and Daniel Wang began preparing as early as last spring. When students in the Klavier (advanced piano) class discussed potential themes for this concert, they realized that they were all learning pieces from different eras.

“I’ve never seen anything like this. Usually, at recitals, the pieces are mostly romantic or classical,” Wang said. “We had a really balanced recital this time, so we were thinking, ‘Hey, we could create some sort of connection between the songs. We could talk about how the music evolved from baroque to contemporary.’”

The opening baroque piece, J.S. Bach’s “English Suite No. 2 in A Minor,” was written in the 1710s for the harpsichord, a popular instrument at the time, but the piano translation that Ibalarrosa played exemplified “the most cheerful and easygoing side of the key of A minor,” according to the Netherlands Bach Society. When piano junior Madison Yan hears baroque music, she enters “another world”: a church filled by soft piano and sunshine.

“Baroque music is so peaceful,” Yan said. “I know a lot of people hate it for no reason. A lot of music is emotional and dark, but baroque music is so pure, like you’re floating in it.”

The classical movement, starting around 1750, was emblematic of the European Enlightenment: a return to Roman and Greek classical ideals and the promotion of rationalism, order, and harmony in art. Felix Mendelssohn’s “Piano Quartet No. 1 in C minor, Op. 1,” performed by Wang—along with strings seniors Priscilla Pang, Finn Amygdalitsis, and Elliot Weber—combines a mixture of romantic energy and classical precision with its “drama to spare.”

“If you’re playing a classical piece, it should be kind of sharp,” Liu said. “It shouldn’t feel muddy since you’re trying to imitate the style of the classical era, but there are also things that you may have not have known, like what the composer wanted the piece to be for or the situation that they composed it in. A composer might have completed something when he was in heartbreak, and you never would have seen it as a heartbroken piece until you actually read about it.”

Piano junior Jason Ibalarrosa and vocal senior Isabella Caggiani perform Johannes Brahms’ “Vergebliches Ständchen,” a humorous dialogue between two lovers. “The male is trying to seduce the female, and the female is not having it” said Caggiani, who sang both the male and female parts.

The romantic response to classicism encouraged the abandonment of reason, a return to absolutist political structures and glorification of the autocracy. The movement gained traction in the wake of Napoleon’s revolutionary conquests throughout continental Europe. While world leaders negotiated for territory at the 1815 Congress of Vienna, the emotionality of an earlier world unmarred by industrialization—a natural world—seeped into music.

“Of course, the baroque and classical eras are both great, but the romantic era is the one I feel a real connection to,” Wang said. “Because the romantic era is defined by more emotion, it has more feelings and more freedom to it.”

The contemporary era, in contrast, is a time of exploration into unknown forms, the release from structure that many of the old masters created. Lowell Liebermann’s “Gargoyles,” for example, is described by author James Elkins as a “demonic march.”

“Good music doesn’t have to be pretty,” piano junior Izumi Yasuda said. “For example, most people would not say [‘Gargoyles No. 4’] is pretty. It’s very atonal, but it’s so cool. The techniques and the emotions are more connected.”

As audiences watched the journey of music through time, performers also got the chance to reflect on their own development as artists.

“[I’ve grown] immensely,” Liu said. “I remember coming [to high school], I really didn’t have a passion for music, but when I started at Dreyfoos, I was suddenly surrounded by people who actually like music. By talking to them and listening to them play, I started to realize the merits of music, and, over time, I developed a passion that I think right now is at its peak.”