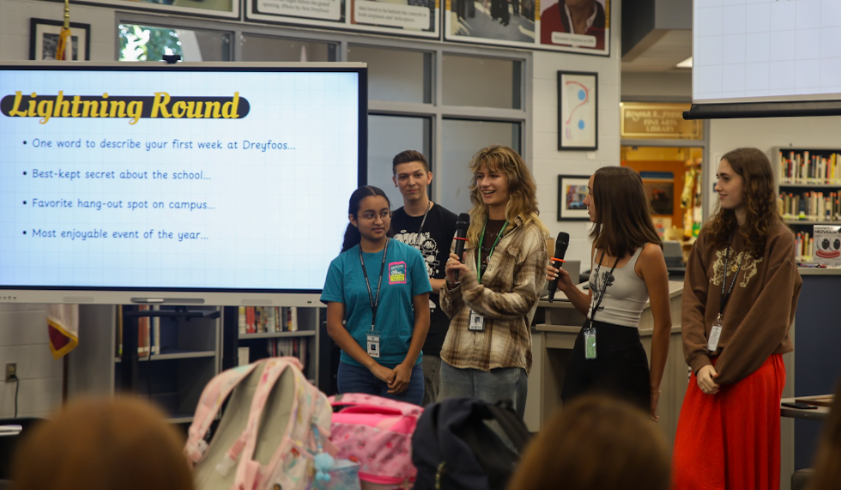

Guest dance teacher Kenny Easter began the partnering class by demonstrating the “promenade” — a move where the leading dancer holds the other dancer by the waist and leg, spinning them slowly while they hold themselves on their pointed toe.

To instruct the dancers, he tapped a dancer on the shoulder to bring her in front of the mirror. He held the dancer by the waist, pulling her right leg up while her left was on pointe.

Mr. Easter demonstrated each movement with a different dancer, each one offering their silent consent as they followed through with the move. However, students and staff in the dance department are beginning to address a gray line: the discussion of “enthusiastic” consent in the Pas De Deux class.

“Pas de deux,” the French term for ballet between two partners — one leading and one following — is an invitational class that dance dean Heather Lescaille teaches. Dancers in the follower role are grabbed, touched, and gripped at the waist, arms, and legs, causing teachers to address whether or not a student is comfortable with a certain movement.

“Consent means you have to ask if there’s something uncomfortable you’re doing, or even something comfortable,” dance senior Robin Burger said. “No means no (…) anything that is not yes (is no).”

Currently, there are no curriculum-based instructions on how students should ask each other for permission to touch each other in an intimate manner.

According to anti-violence news source RAINN, enthusiastic consent is vital to the consent process as a whole. Enthusiastic consent means looking for the presence of a “yes” instead of the absence of “no,” ensuring each partner is on the same page.

“I’m having to explore changing my language in general, but what I try to do with the kids is remind them I’m teaching classical ballet technique,” Mrs. Lescaille said. “At the beginning of class, I always say ‘If I say something that offends you, just let me know.’”

Mrs. Lescaille says one of the first things she had to change was letting students deny the invitation to the class if they were uncomfortable with the curriculum, which was previously mandatory for some dancers.

“The ballet world is gonna get hit with (consensual education) first because of the language we use and the way it’s taught,” Mrs. Lescaille said.

For students like dance senior Michelina Coates, physical contact with other dancers can cause discomfort.

“It’s a lot of touching. As a dancer and as a person, I’m not really comfortable,” Coates said. “It’s difficult as a dancer because you have to push yourself in different ways. When we’re not doing that, you can’t progress, so it’s pushing me back.”

According to the Boston University School of Law, there are only eight states in the U.S. that are required to teach consent, and Florida is not one of them.

Students like dance senior Savonya Haliburton develop their own methods to help the pas de deux class feel more comfortable. Haliburton believes consent should be taught at a young age to teach dancers how to create boundaries for their partner.

“We thank the teacher, and we thank ourselves for the class,” Haliburton said. “We should establish that in ballet. Before we start class, you ask your partner, ‘Is it okay if I partner with you today?’ And we establish some rules if there’s rules that need to be in place between (partners).”

Intimacy and consent coordinators have been introduced to ballet studios like Scottish Ballet, according to the New York Times article, “Bringing Consent to Ballet, One Intimacy Workshop at a Time.” However, most students have an unspoken notion of consent with their partners and choreographers, but for some, that’s not enough.

“A lot of the time the teacher will demonstrate where to grab when you’re lifting or partnering,” dance senior Alyssa Dicembrino said. “If it is uncomfortable for someone, that can get fuzzy because sometimes people are nervous to say something.”

Planned Parenthood educators like Malinda Britt have created consent-oriented dance workshops and are promoting the use of explicit verbal consent in dance.

An example of Britt’s workshop is answering questions like “Do you like pineapple on pizza?” with “No” and responding with “Thank you for your no.” These questions aim to clear the air when it comes to addressing consent in a serious manner, like whether or not they are comfortable with being touched.

Dicembrino has choreographed dancers and non-dancers alike during Spirit Week, and makes communication a key part to her choreography.

“Communicating and being like, ‘If you’re uncomfortable, let me know,’” Dicembrino said. “Sometimes I’ve had it where teachers will touch a student and be like, ‘Is this okay?’” and (…) ‘Express if you’re uncomfortable.’”

The dance department has worked on creating a trustworthy environment that values consent and comfortability within the classroom. Given they’ve all known each other for three or four years, Mrs. Lescaille describes the group dynamic as a “family.”

“Consent ties into that element of teamwork and being aware of each other and respectful of one another,” Mrs. Lescaille said. “The same goes for us as a faculty, knowing where everybody’s level of comfortability lies.”

To best demonstrate their trust, each dancer advocates for the use of communication. Using consent can elevate trust to an enthusiastic degree.

As the dancers continue class, communication is present. With every mistake and stumble, partners ask one another if they’re okay and if they’d like to continue.

“I think one of the things we try to enforce in the dance department, but just as a general part of their training, is common courtesy for one another because you do have to work together so much,” Mrs. Lescaille said. “Consent falls in line with that of having courtesy if you’re dancing with a partner or you’re dancing with 25 other people.”