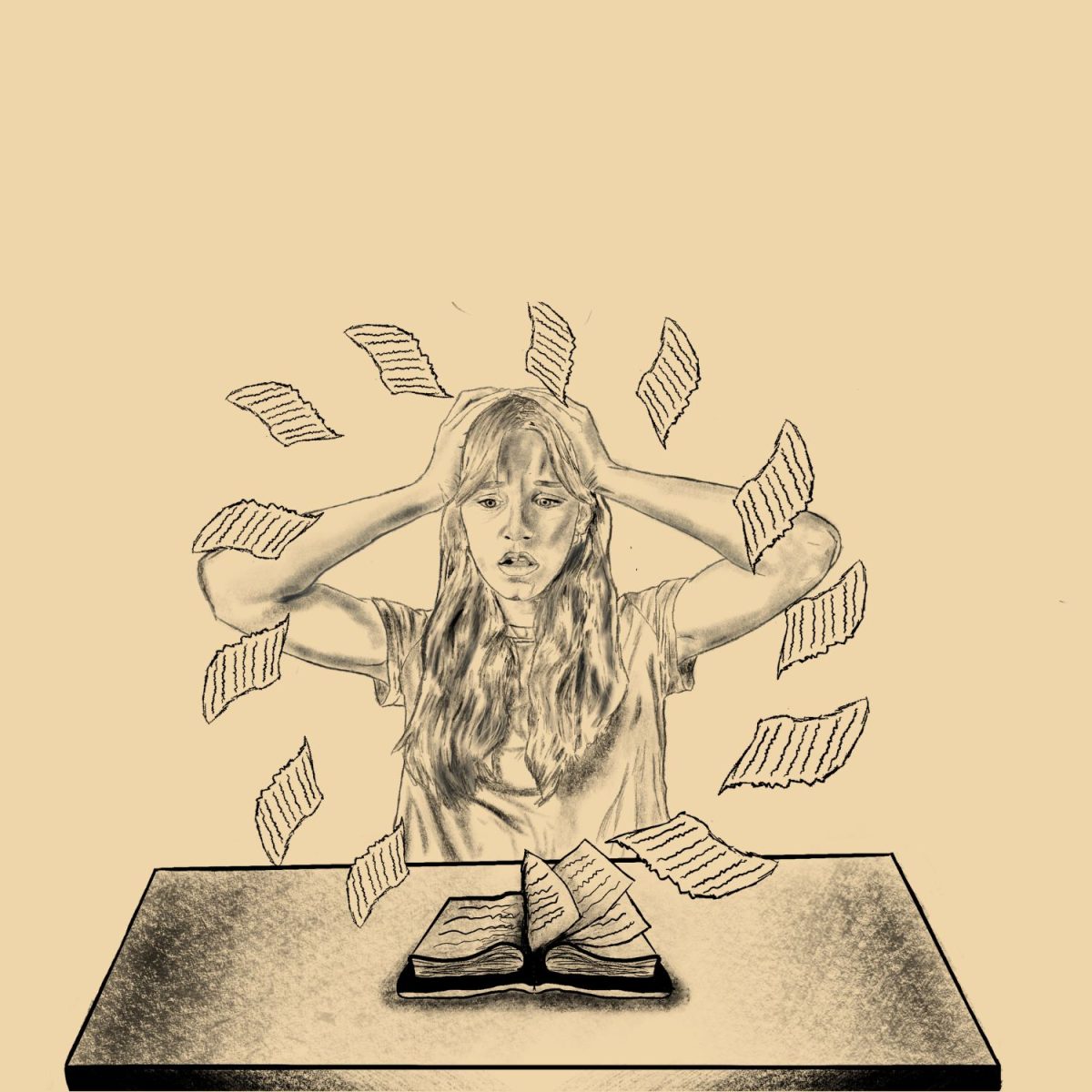

Silence descends as the judges signal to start — this silence is broken by song, stirred through the notes of a clarinet, fractured by the playing of ivory keys, and ruptured as emotional power unhinges through monologues. Juries, evaluations of artistic progress that occur at the end of each semester, have always been a staple of Dreyfoos’ evaluation of artistic growth. But they have been changing ever since crowded halls have turned to Google Meet icons.

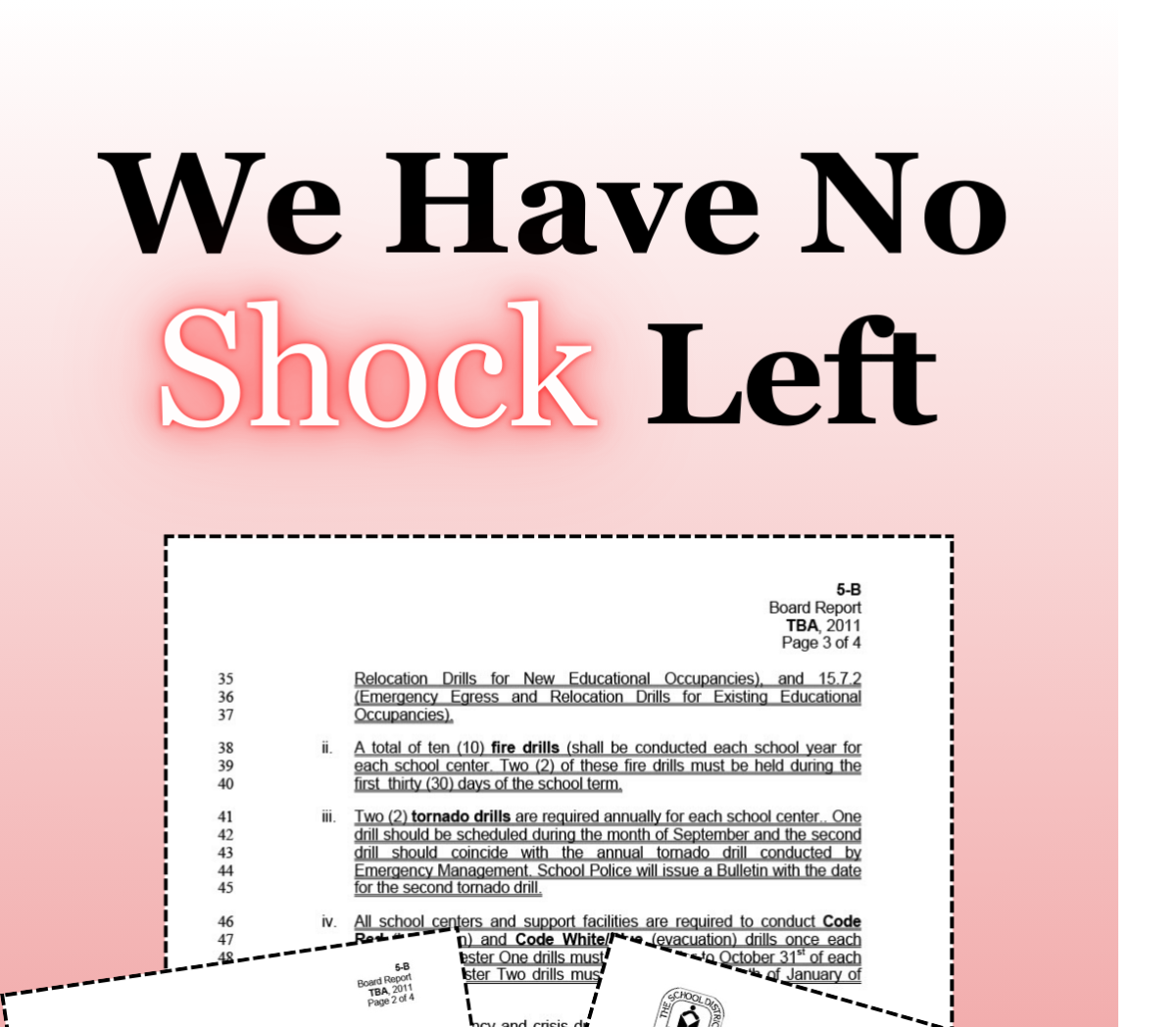

The dance, communications, visual art, and digital media departments are not assigning juries at all this semester. As for the theatre and music departments, first-semester juries have been altered to accommodate remote learning conditions.

For band majors, all juries are virtual. Instead of a live, in-person evaluation, students have a month to pre-record their chosen song and attach it to the corresponding Google Classroom assignment.

“With recorded [juries] you have as many chances as you want to get it perfect,” band sophomore Bobbi Zimmelman said. “When it’s live, the pressure’s on. I feel like I have to get it right the first time and the way I want it to be when it’s live, but recorded, I know that I have as many chances [as I need] so I keep messing up.”

Zimmelman was practicing consistently up until her jury on Jan. 25, and typically rehearsed five to six times a week. The song she chose to play on the clarinet was “Solo De Concours” by André Messager, which she originally received for a solo back in August. Since she could not perform due to the pandemic, she chose to perform it at her jury. Despite her familiarity with the song, a challenge for Zimmelman has been adjusting her performance to reside within her bedroom.

“My bedroom feels like a more casual setting than if we were doing juries in the band room at school,” Zimmelman said. “It makes me less focused because that’s my room where I do everything in my life and it’s where I practice, so it feels like a practice setting, not a performance setting.”

Similarly, strings juries have been moved online, giving students an opportunity to perfect their recordings before having to submit them, rather than having to perform live. For some students, however, finding a peaceful spot with good quality to record has proved to be difficult.

“I’m performing from my cabana, and obviously the acoustics are not too good,” strings senior Gerrit Felton said. “I feel like playing in front of judges or in front of an audience allows me to play better than I typically would if I was just playing in front of my phone screen recording myself.”

Felton’s solo piece, “A Cello Suite 1st Movement” by Gaspar Cassadó, was only one of three components of his jury. The others, arpeggios and three scales, are equally as important when it comes to the final grade and remain the same as previous years.

“[Preparing for my jury] was the same as I usually practice for any of my music repertoire,” Felton said. “I go through and fix my intonation and tempo, use a metronome to try and go slow with the speed and tempo, and then [in] the end, it’s about musicality.”

For vocal majors, students in person conducted their juries similar to previous years: a live evaluation at school dressed in elevated attire. In-person students had to wear a mask during their jury. Virtual students still gave a live performance, though it was done through a Google Meet.

“I would prefer to do it online because I feel like it would be much less stress,” vocal sophomore Mitchell Thai said. “[But] I feel like in-person makes school feel more normal to me and makes me feel justified for going to Dreyfoos.”

For Thai’s first semester jury, along with other sophomore vocal majors, he had to memorize three songs: one in English, one in Italian, and one in German. Then, he performed whichever song the judges chose, which was Thai’s German song. Thai also had to memorize the translations of the songs and know the context of the piece. In order to reduce stress, his preparation schedule took up every day of the week, leading up to his in-person jury on Jan. 26.

“I feel like being in the same room with the judges is a whole different story because they can read your body language and they can judge you more severely,” Thai said.

The jury process for theatre differs between particular tracks, but those in the acting track have to perform a monologue and prepare a character analysis document. There are no mandatory lab hours (time spent outside of class on theatre productions and shows), which makes the grade based solely on the performance and “prep” form.

“Usually everybody goes into the [Brandt Black Box Theater] and watches [the juries], but this year we had to all join the same Google Meet and then three teachers judge it,” theatre junior Grace Trainor said. “I performed it in school so I had to do it in front of the camera with a mask on, [which] was definitely different from years in the past as well just because you have to deal with the weight of that on your face and trying to use your diction to communicate.”

Trainor performed a monologue from Shakespeare’s “Henry VI, Part 1.” In preparation, she paraphrased Shakespeare’s words so she could comprehend it better, along with relating the characters to aspects of her personal life.

“I was considering doing the virtual jury because I thought it would be easier without a mask on,” Trainor said. “But for me, there’s just this intimacy of live theater and being in person and seeing the reaction of the audience and just really being in a space [that] gets your nerves working.”

Piano juries follow a similar outline as previous years in which students have to play a solo, scales, and then prepare a speech about their piece. However, adapting to social distancing guidelines, they too have been moved online, bringing about a newfound sense of “freedom” for students.

“I think it was less nerve-wracking, but it also didn’t really feel as serious as juries in the past,” piano junior Alice Chong said. “You [are] able to just do your own thing and record it at your own leisure, rather than having the pressure to perform it live.”

For Chong’s piece, “Improvisation Homage to Edith Piaf” by Francis Poulenc, Chong had to constantly rerecord it, taking almost three days to get the perfect video.

“This year I felt a lot less prepared than other years in the past,” Chong said. “[However,] I still think it’s beneficial because Ms. Katz still gives out critiques that help you improve on how you play.”

Even in the new digital format they have adapted to, juries still provide a useful learning experience for students, helping them to expand their artistic skillset.

“[Juries] allow me to take all my practicing, especially fundamentals, and put it all towards one product: my solo,” Zimmelman said. “[They] give me an opportunity to perform which is always super helpful. It allows me to expand my repertoire and learn new pieces.”

![[BRIEF] The Muse recognized as NSPA Online Pacemaker Finalist](https://www.themuseatdreyfoos.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/IMG_2942.jpeg)