Imagine this…

You’re a senior at Illinois State’s U-High in Bloomington, Illinois. You’re two and a half hours from Chicago and fringe bangs are in and the university coffee store has great printers. You only know this because tonight, your friend Hudson from the public high school prints the whole grade a map that you’ll read from the dashboard to direct Leslie— who’s driving — to Hudson’s farm. From there, you head to the cornfields set up with kegs and Nirvana blasting from the radio. Buffy — in the backseat — notices a car behind you. Probably lost like us, you think. And then, just as Buffy puts Leslie’s car keys into her purse and you jump into the sea of lights and kids and music, the car behind you turns on its sirens and your entire grade is running through stalks of corn, hoping to get lost from the cops. Well, your entire grade minus you and Leslie, who forgot that Buffy (now running) took the getaway car’s keys.

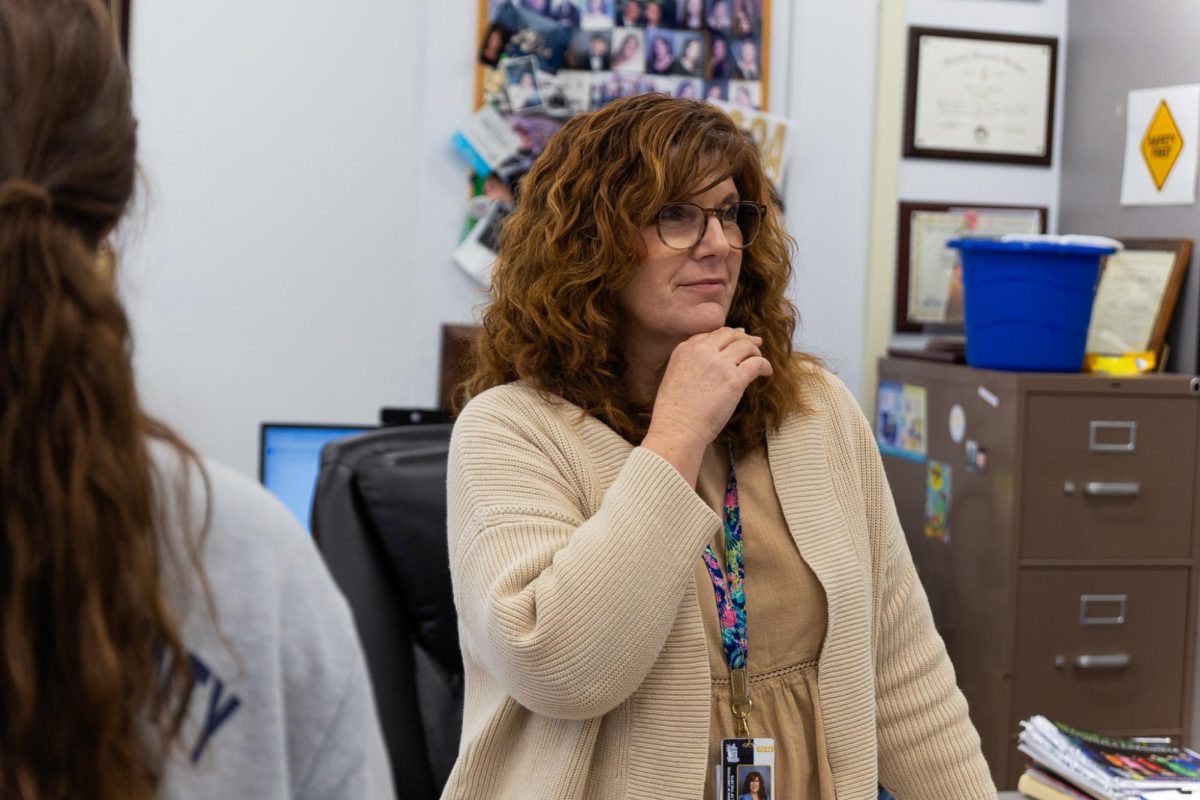

Mrs. Zietz busted Hudson’s entire cornfield party of Bloomington, Illinois and she still hasn’t forgotten.

And, well, neither have we. The Cornfield Story is told so often we call Buffy-isms in class — a sort of rite of passage for sophomores in World History. And though most teachers have a staple story of which to warn students against, this anthology of memories running through the farmlands of small-town America is different.

Mrs. Zietz teaches only in stories. Her cornfield chase comes right after Cleopatra’s scandals.

“I judge myself — the biggest thrill I have is kids that are freshmen that didn’t take AP, or took AP as freshmen and they weren’t successful in it, [that] find success in here. That’s how I judge my worth as a teacher.”

“And I guess I kind of have that view for the world. Why can’t we bring up ‘the ‘bottom’?” she asks, referring to the entirety of world history.

Unlike average AP classes in which college-level material is taught in a high school manner, Mrs. Zietz teaches it like we are already in college. She walks around, tells stories, drinks her coffee (two to three cups in a morning class), and expects us to write it down. Or not.

It’s a class in which studying is put into students’ hands but the teacher’s pass rates are the highest in the nation. Her 2019-2020 fourth-period class had a 100 percent pass rate, rare even among academically competitive schools.

“People that come in here gifted with 160 IQs or whatever, and every resource in the world — their college counselors — they don’t need me,” Mrs. Zietz said. “They get fives on the exams, go to four-year universities, those kids are fine. But the kids that don’t have confidence, have never taken an AP class, can see that this isn’t for other people. This is for you, too.”

This past summer, as the Black Lives Matter movement ignited around the US, Mrs. Zietz took to her Instagram — where she posts about Tom Zietz, her golden retriever puppy, and relatable school memes — to voice her support for the protestors.

She registered as a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). She asked for book recommendations from black authors. She argued with family members on Facebook, defending black citizens.

On the first day of my sophomore year, Mrs. Zietz announced a test. And then she announced that she does not teach the white man’s history.

“Looking back, I grew up in a crazy conservative area,” Mrs. Zietz said. “But I didn’t know when I was young that it was conservative. The model of my hometown was kids should be seen and not heard. And so we had a lot of freedom. I just accepted people for people.

“Then I started teaching. My very first students were ESOL [English to Speakers of Other Languages] students, so my room was 100 percent diverse in multiple ways. And sometimes, I would be the only white person in the room.” (Mrs. Zietz had only one black classmate and two Jewish classmates in her hometown, she recounts.) “I remember how other teachers and administrators were talking about my students and I would get so outraged. Nobody had any expectations for them to do well.

“And then I read that silence is interpreted by people of power as approval. And I really changed my view and how I behave. This summer, after George Floyd, [I realized] to be silent is approval. We need to protect everybody. We need to make room.”

Within Mrs. Zietz’s classroom, this is how it is done. We used to call her, affectionately, a second mom.

“She thought of her students as her literal kids,” dance junior Addie Joslin said. “She treated us so good. The one time I needed help on a test, I went to her for tutoring one morning and on the next test and I got the best grade I had gotten all year. She literally wrote me a handwritten letter saying she was proud of me.

“I still have it.”

In response to whether the ‘second mom’ title is scary, Mrs. Zeitz said, “No pressure … Like, joy. Because [I] didn’t have kids, [My husband and I] chose not to, so it’s fun to have influence.”

“I like it. We remember our relationships.”

When I ask Mrs. Zietz whether she can tell me a story no one knows about her, she thinks for five minutes. It’s clear she keeps no secrets in her classroom.

“I used to skip school, a lot,” she confesses.

“I don’t think I’ve ever had a sub in your class,” I say.

“Oh, I’m totally different now. I don’t like it. If I miss school, it’s thought out plenty ahead of time.”

I look around Mrs. Zietz’s classroom while she ventures into a story about how she almost ended up living in Hawaii after a family vacation. Before COVID-19, her desks were pushed next to each other so she could walk around and socialize about the Umayyad Caliphate.

From the upper right corner of her room — my old seat — you could see her Jolly Monk shrine and bookshelves all at once. Now, it’s much more bare. Except that in this classroom, the stories are the only decorations needed.

“Maybe I’d be in a surf shop today in Hawaii, wearing the puka necklace,” she jokes. “That’s not bad. Everybody’s happy in Hawaii.”

And for the record, Buffy returned the car keys.

Mrs. Zietz never went to a cornfield party again.