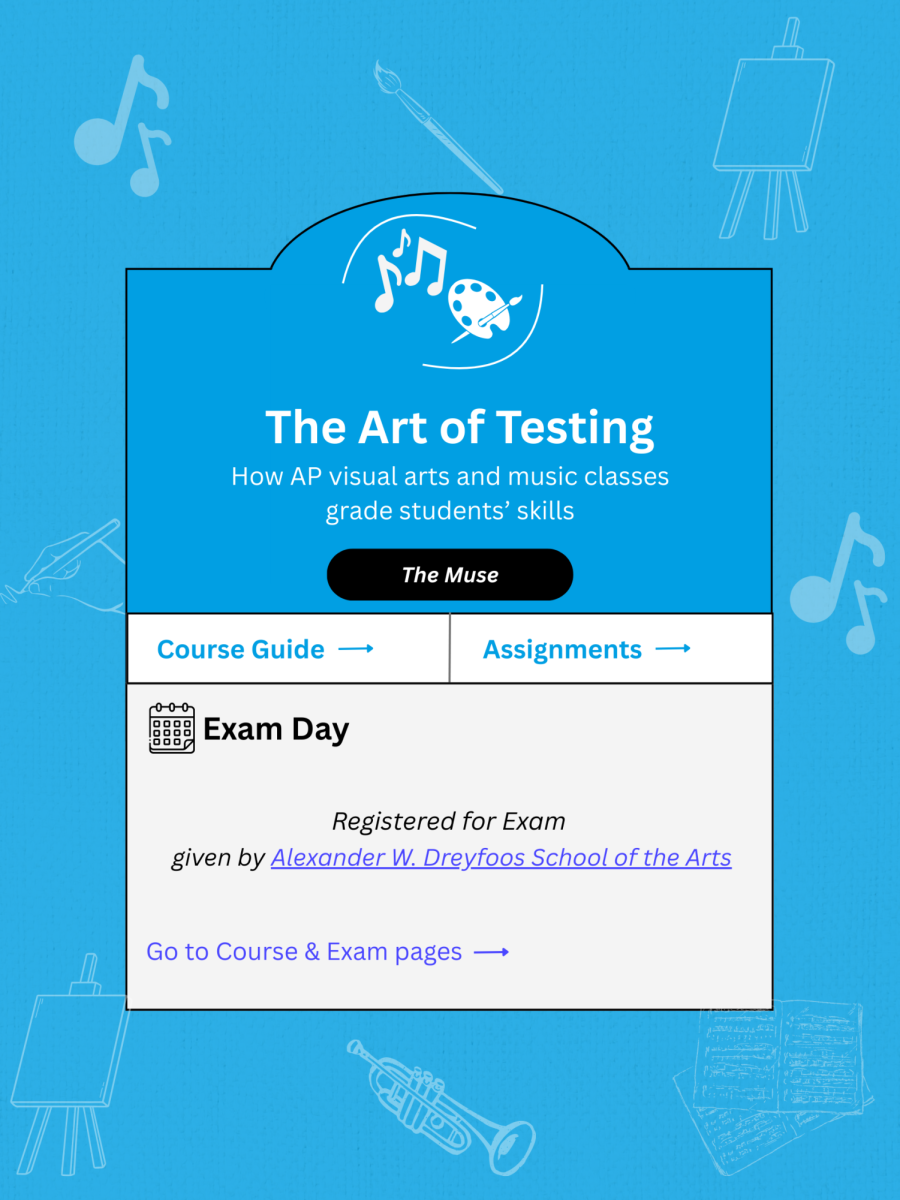

Students Can Choose Their Safety; Teachers Cannot

Teachers are being asked to teach from the classroom. As a result many have chosen to leave the school.

Brett Burkey, former social studies teacher, enjoys nature on a run through Montauk Point State Park. During his retirement, he has spent his time doing what he cares about most: staying fit and healthy. He has taken this opportunity to turn his COVID-19 affected retirement into an enjoyable time to do activities he loves.

Former Assistant Principal George Miller left the faculty parking lot in his red Corvette for the last time with big plans: Touring the country to see his trademark football team play. Former science teacher Sherry Little kicked off her retirement by scheduling an Amtrak landmark trip of the United States from Chicago to San Francisco. Former history teacher Brett Burkey just hoped to safely care for and spend time with his elderly relatives.

Every year Dreyfoos loses beloved staff to retirement. This year’s list featured some especially big names, from administrators who have kept campus running for decades, to new teachers whose presence have shaped students in their limited time. Though, in addition to the scheduled retirement of many, some unexpected faces will be missing from the halls.

Students have a choice as to whether they will return to campus amid the COVID-19 chaos. Teachers do not. It has been nerve-racking for faculty to return to the job aware of inherent risks that being around others poses, particularly for those with higher vulnerability to the virus.

“When I found out that we were coming back in person … sooner rather than later, I was extremely nervous,” creative writing teacher Brittany Rigdon said. “With the research that I’ve done, looking at dashboards from reputable sources, the numbers are still quite high.”

In order to address these concerns, the school and district have implemented a number of safety measures that have proved successful thus far. Still, many faculty members are looking to take extra precaution. Band teacher Pedro Hernandez decided to retire early, a loss for students like piano senior Amina Idrisi who recall his class fondly.

“I remember during the first class that I ever had with him as a freshman, he stopped for a moment and told us that we were all his students now, and if we needed to talk about something we could always go to him,” Idrisi said.

The school district has implemented a system to prevent high-risk individuals from returning to work in-person. Teachers may apply to be approved for virtual teaching by submitting information about their personal or familial medical history. However, many found this to be an invasion of privacy.

“It required getting a letter from my doctor saying I met those criteria, and it had to be very specific,” science teacher Marilynn Pedek-Howard said. “I had to say specifically what [criteria I met].”

As a high-risk individual herself, Mrs. Pedek-Howard was fortunate enough to be approved for virtual teaching, but the process to reach this verdict wasn’t simple. The application highlights five reasons for requesting to stay home listed in order of their severity that each teacher must conform to. These include being disabled, having a pre-existing medical condition, being 65 years old or older, having an at-risk family member, or otherwise feeling uncomfortable with returning to school. It is in the school’s hands to decide whether they can logistically provide the accommodations necessary to issue an approval.

Detailing her work-from-home experience, Mrs. Pedek-Howard notes that it is nothing compared to the classroom.

“At school I had my smartboard and I could get up, stand, and move around,” she said.“Here at home I’m more stuck in one place.” Nonetheless, what she misses more than anything is the students and the energy they brought to the room.

“If we were in in-person chemistry, you sat at the table with four other people, so if you had a question and I was busy helping somebody else, you could ask them,” Mrs. Pedek-Howard began. “Or if you were through with your work you could have a little conversation with the person next to you about what they were doing on the weekend. Now you don’t have those relationships.”

In this setting, Mrs. Pedek-Howard has adjusted her typical teaching routine to accommodate for learning and social changes. She has made a point to ensure neither was compromised, administering chemistry labs from home by both utilizing experimental software and planning at-home projects that engage her students with their curriculum in an interactive way.

“What I have in my office is six computers set up, and each one of the computers is a different breakout group,” Mrs. Pedek-Howard said. “So I just use my little rolling chair and I go from computer to computer and check in with people like I would do in class.”

As the school’s reopening approached, Spanish teacher Sarah Smith also applied for distance teaching in order to prevent any risk of transmitting COVID-19 to her high-risk family members. Despite being cleared by the district to do so, the school was unable to fulfill her request. So when asked to choose between her two loves — teaching or family — Mrs. Smith made the hard decision of temporarily sacrificing her occupation, salary, and benefits to take a leave of absence.

“The reason we live where we live is because my family is important to me,” Mrs. Smith said. “Within a small three mile radius my sister, her kids, her husband, and my mom live. My mom is over 65, which makes her high-risk, and one of my nephews is at extremely high risk. He had open heart surgery at four months old [and lives with] a whole slew of medical issues. As a family we talked about it, and the upshot of it was we could no longer be in our family bubble if I went back to work.”

With high risk people in her inner circle, Mrs. Smith knew she couldn’t take the chance of returning in person. The decision was not easy, as she already misses the students she began teaching in the first weeks of the semester.

“This will be the longest leave I’ve ever taken, including maternity leaves — and I have four children. I’ve never taken this much time off from teaching, ever. I’ve been doing it in some way, shape, or form since highschool. I started tutoring in high school, and I taught and tutored through college. I taught a college level class at University of Florida, high school, and middle school.”

Other teachers have faced similar challenges to Mrs. Smith and Mrs. Pedek-Howard, but haven’t let it get the best of them. In true Dreyfoos spirit, they’ve all found ways to make the most of the situation at hand.

Mrs. Smith refocused her free time to center around self-improvement and community outreach, explaining, “I don’t like to sit around and do nothing. My personal goal is to do a lot of professional development,” she said. “I [also] found an organization that delivers meals on Fridays to Jewish members in the community, Shabbat meals.”

When the teachers interviewed in this article were asked what they miss most about teaching in person, they all said the same thing: the students. It came down to a simple decision of what is best for their health and that of those around them.

“If it were a choice of teaching or not teaching, I would say teach,” Mrs. Smith said. “But if it’s a choice between my family and my job, I have to go with my family.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Dreyfoos School of the Arts. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Brenda Johnson • Nov 2, 2020 at 10:34 am

What an eye opening look into the heartwrenching decisions todays educators are being faced with. Thank you for sharing their stories Rachel!