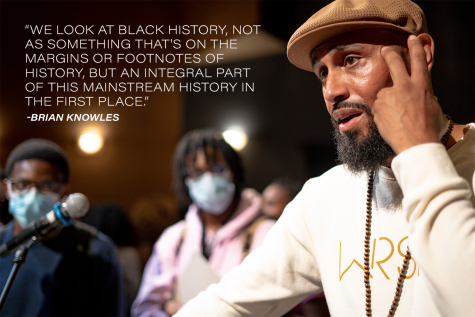

Hanging around Brian Knowles’ neck is a dark wooden necklace with an African continent pendant at the bottom. This necklace serves as an allusion to Mr. Knowles’ message: the importance of shining a light on the diversity of Black history rather than the oppression Black people have faced.

“I really think you miss out on the pure humanity and the diverse experiences of black folks when we focus on the external oppression that we suffered,” Mr. Knowles said when discussing the importance of teaching Black culture.

Mr. Knowles is the manager of the Office of African, African American, Latino, Holocaust, and Gender Studies within the School District of Palm Beach County. Black Student Union (BSU) invited him on campus to give a speech as a part of their spirit week. Teachers signed their classes up to attend the discussion during first period.

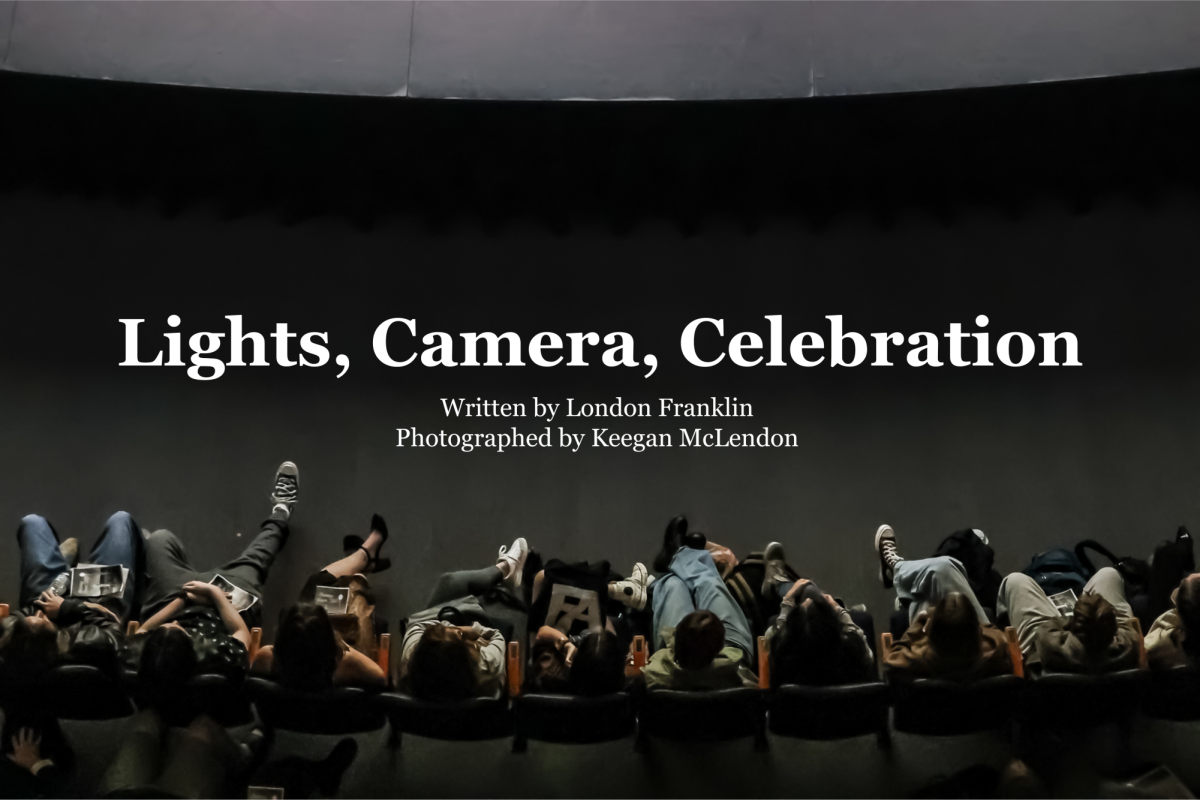

Mr. Knowles opened the conversation by discussing some of the Black stories that preceded the events of slavery and the civil rights movement. He didn’t present a slideshow, yet nearly every head in the auditorium was turned towards him.

Discussing everything from African culture to the role of Black women in Palm Beach County history, he emphasized the importance of representation in schools and education as a whole.

“Everybody needs to be represented because, first of all, I have to see where I fit in, where I’m affirmed first,” Mr. Knowles said. “As a student, right? I want to feel safe. I want to feel valued. I want to feel affirmed. I want to feel humanized. And a way to do that is being able to see myself and engage with something that I can feel.”

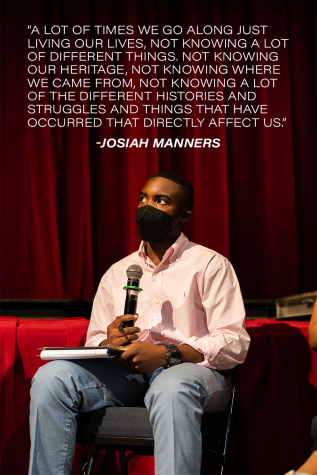

The conversation also featured a panel of students, including communications sophomore Josiah Manners, who asked questions regarding representation, the origins of Black History Month, and the differences between race, culture, and ethnicity.

“(I’m) starting to become more and more vocal and active in regards to education,” Manners said. “I’ve been raised in a house of educators. The biggest thing for me was taking further action, not (only) educating people, but also, you can’t educate other people if you don’t know yourself.”

Manners and Mr. Knowles have known each other for years. They met at the Conservatory School, where Mr. Knowles helped Manners’ 7th grade class with their projects on African American history. Manners described Mr. Knowles as “open” when answering his questions and becoming a “mentor” to him over the years.

“The conversations that I’ve had with Mr. Knowles pushed me to go and do further research,” Manners said.

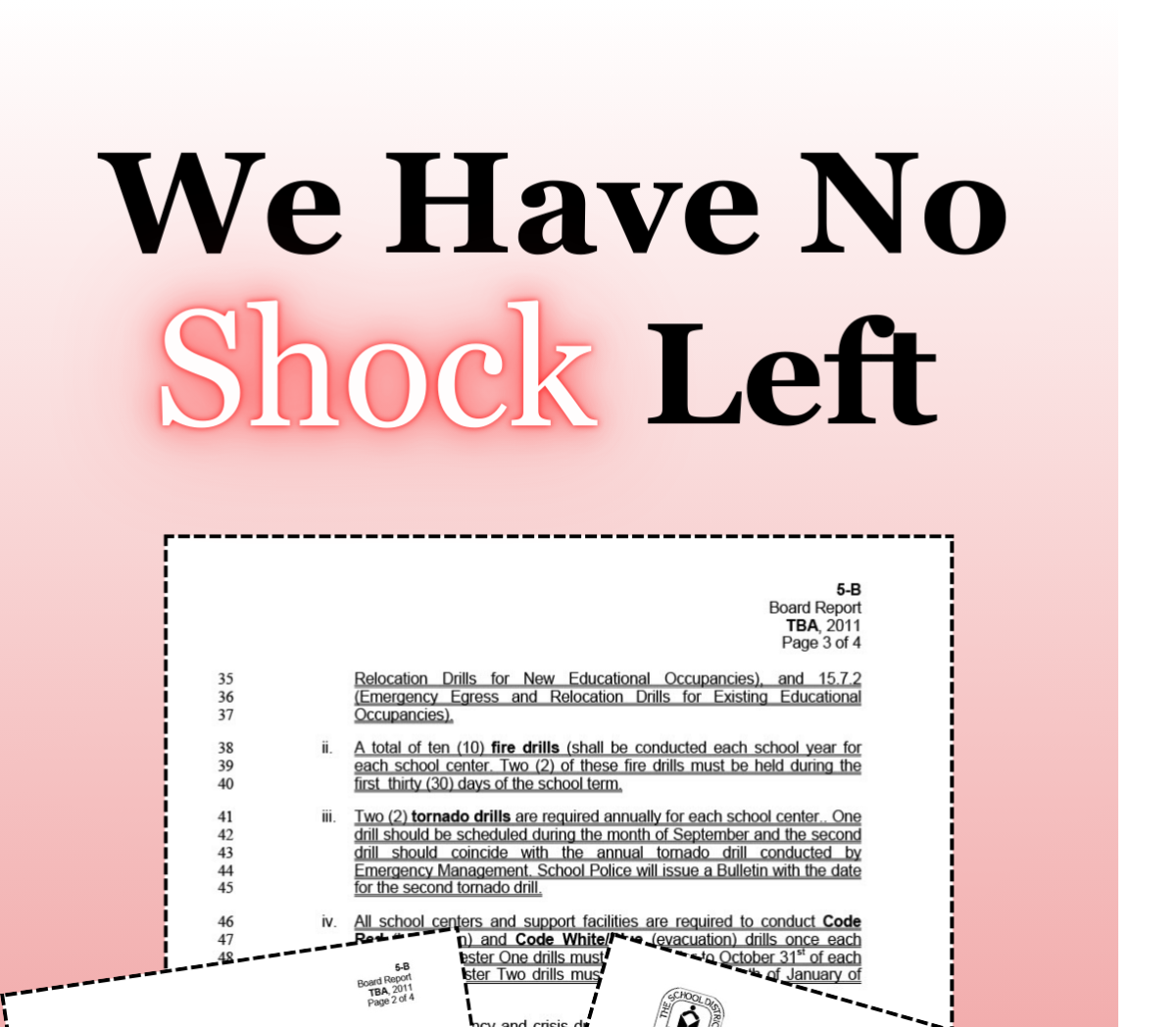

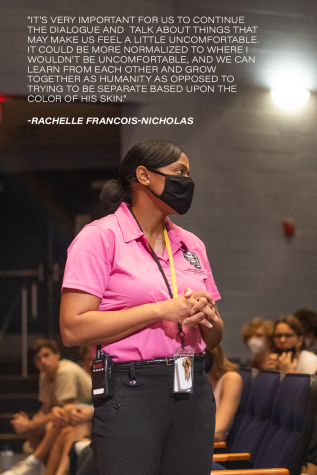

After the panelists’ questions, the floor opened for other students to ask Mr. Knowles questions about Black history and culture. One of the topics brought up was the teaching of Black history in the classroom. When asked about Black history education, guidance counselor and BSU co-sponsor Rachelle Francois-Nicholas hesitated before answering.

“I think that it is minimal,” Mrs. Nicholas said. “As (Mr. Knowles) stated, I think we just need to do a better job of teaching and incorporating more. As a former teacher myself, I found it to be a lot of work looking for key pieces that I can teach students that would keep them engaged and teach them about their history through literature.”

Mr. Knowles was surrounded by students and their questions as the 10:16 a.m. bell approached, he attempted to meet each student’s question with an answer. His conversation with band senior Stephen Uter, in particular, continued past the first period bell and into third period. They sat outside Meyer Hall: Uter, with a paper filled with questions, and Mr. Knowles with a response for each one.

Mr. Knowles credits a lot of his philosophy about teaching Black history to conversations with elders and people in his community.

“As I dug deeper, there’s so much more to uncover,” Mr. Knowles said. “You just start to pull back those layers of the experiences of folks versus just the oppression that we hear about (in school). I came to the conclusion, like, ‘wow, so we just hear the stories of oppression because it’s a safe, palatable way to have representation.’”

Mrs. Nicholas echoed the same sentiment when it comes to education on topics like the difference between race, ethnicity, and culture, or the difference between the term African American and Black.

“It’s very important for us to continue the dialogue and talk about things that may make us feel a little uncomfortable,” Mrs. Nicholas said. “It could be more normalized to where I wouldn’t be uncomfortable, and we can learn from each other and grow together as humanity as opposed to trying to be separate based upon the color of his skin.”

Manners emphasizes the importance of dialogues surrounding the history of minorities and its effect on students.

“A lot of times we go along just living our lives, not knowing a lot of different things,” Manners said. “Not knowing our heritage, not knowing where we came from, not knowing a lot of the different histories and struggles and things that have occurred that directly affect us.”

By 10:45 a.m., Mr. Knowles sat alone outside Meyer Hall. All the students had left, and the group photos had been taken. It was much quieter, but Mr. Knowles was still animated as he discussed the future of Black history education.

“We’re starting to incorporate more of those stories,” Mr. Knowles said. “We look at Black history, not as something that’s on the margins or footnotes of history, but an integral part of this mainstream history in the first place.”

![[BRIEF] The Muse recognized as NSPA Online Pacemaker Finalist](https://www.themuseatdreyfoos.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/IMG_2942.jpeg)