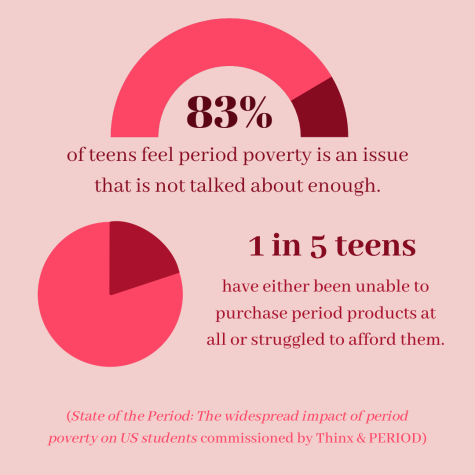

The period: something that affects half the population (and the majority of the school). Despite the number of people affected, resources can be limited for those who need them, including up to two-thirds of low income women in the U.S, according to the Journal of Global Health Reports.

According to the same source, period poverty is a term defined by a lack of access to menstrual products, hygiene facilities, and educational opportunities required for a person’s menstrual cycle. According to The University of Alabama at Birmingham, the issue is caused by a lack of affordable supplies. This is considered to be a public health crisis by Planned Parenthood.

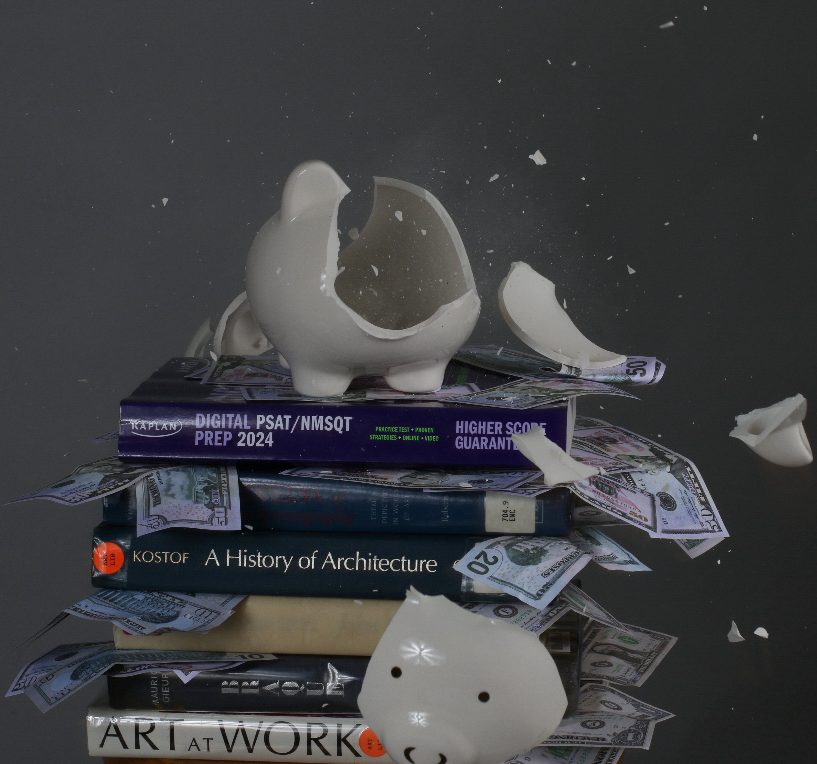

A study conducted by OnePoll found that menstruating individuals spent around $6,360 over the course of their reproductive lifetime (12 to 52 years old), or about $13.50 a month.

Florida is not immune to these issues. According to the World Population Review, 14.79% of Florida lives in poverty, and according to the same study, the percentage of those menstruating individuals are the most economically vulnerable.

Olivia Kapow, a former Suncoast High School student, was able to gather $15,000 in funding to eventually install a period product dispenser at Santaluces High School. Santaluces is a title one school, or a school in which children from low-income families make up at least 40% of enrollment.

“It’s hard for women in poverty because even a lot of women’s shelters surprisingly do not supply these products for free, which is absolutely insane,” Kacham said. “A lot of low income students in middle school and high school don’t have access to these products. It’s not a surprise when you think about it.”

According to the Alliance for Period Supplies, period products — while a basic necessity — are still being taxed at the cost of a luxury item in the majority of the U.S. In May 2017, Florida Governor Rick Scott signed a law making period products exempt from tax. Still, the cost of period products means it can place a strain on menstruating individuals in a state in which, according to the same source, one in six women aged 12 to 44 live below the Federal Poverty Line.

The World Bank estimates that 500 million women and girls globally lack access to adequate facilities for menstrual hygiene management.

According to The Borgen Project, a nonprofit organization dedicated to fighting poverty, the average North American woman will use and throw away about 13,000 tampons and pads in her lifetime. The disposable nature of tampons and pads means costs will rack up, with new boxes being bought every month until menopause.

A solution that around 8.7% of menstruators, according to a study by The Public Library of Science, are turning to is reusable period underwear. While it functions the same way as a pad, it is washable, meaning its users do not have to buy more supplies every month.

Period underwear, unlike pads or tampons, is not usually found in most stores, and often sells for a higher price. To counteract both the disposable nature of pads and tampons and the accessibility of period underwear, organizations such as Thinx, a sustainable period underwear company, and AFRIpads, a washable pad company, are selling these products at lower prices in developing countries, 12 cents for a product that will last a year.

However, with a lack of low-cost resources given, some turn to other, potentially dangerous, methods.

According to the Global Development Commons, individuals often resort to using dirty rags when they do not have access to pads or tampons. Those who use this technique may face serious infections related to the cleanliness of the materials they used. But even those with access to clean products may deal with other health issues.

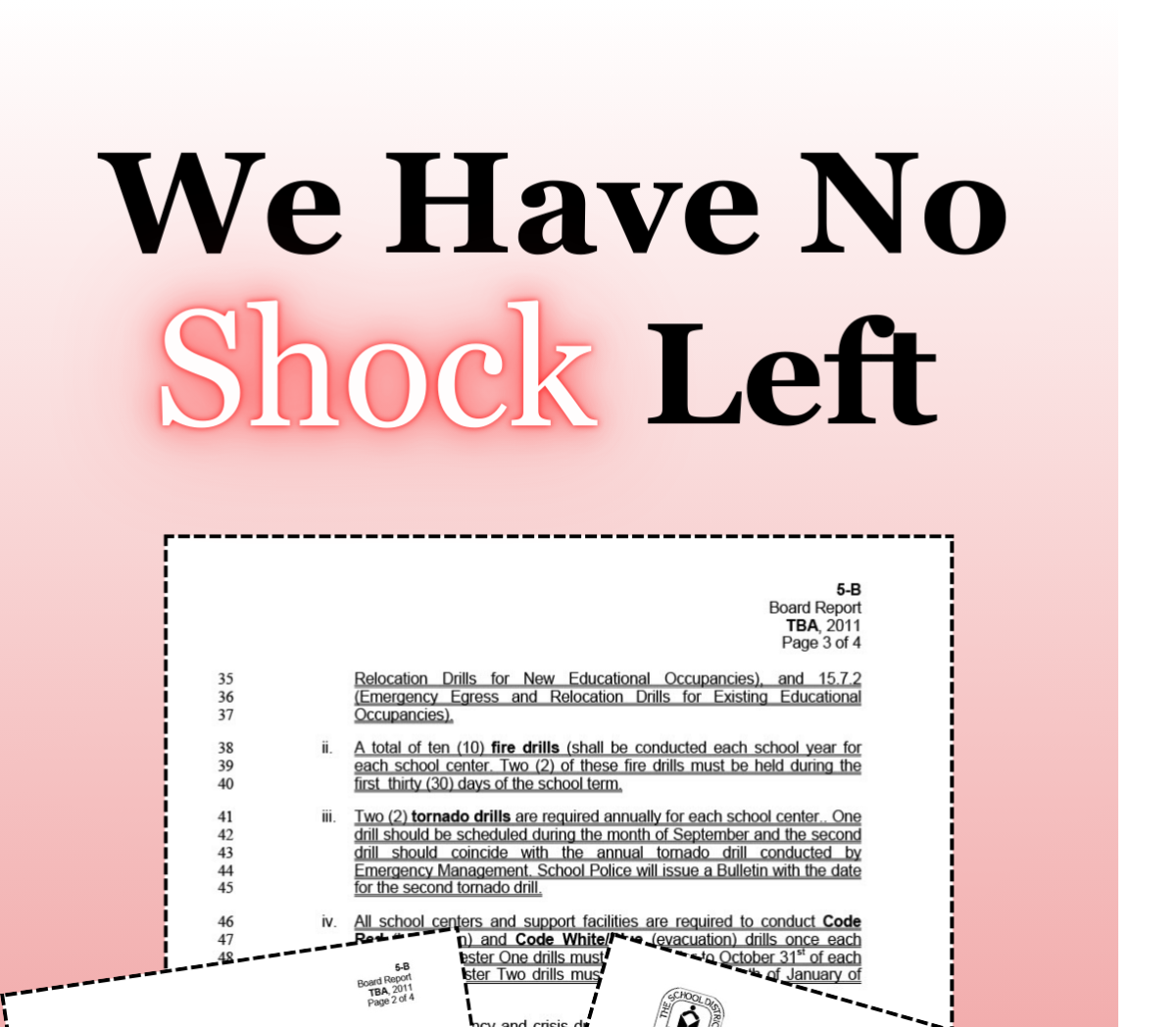

When people cannot afford the supplies they need, they end up using the same products for prolonged periods of time so they do not run out. This can become dangerous when considering that the longer a tampon sits within the body, the more likely it is for the person using it to develop toxic shock syndrome, a life threatening infection that could be caused by extensive tampon usage that affects one to three out of 100,000 menstruating women, according to The Lancet.

The impact of the lack of resources goes beyond physical health. According to a study by BMC Women’s Health, women who struggled with period poverty within the past year were more likely to report moderate to severe depression.

Not only is period poverty correlated with poor health, it may also affect a person’s day-to-day life. According to the Alliance for Period Supplies, in 2019, one in four teens across the country said they had missed school due to lack of period supplies.

“I think almost every girl has been in a situation where they have had to ask a friend for a pad, or they had to make a makeshift pad, and it doesn’t make sense,” Kapow said. “Pads are comparable to toilet paper. They should be at least treated as essential as it.”

According to UNICEF, periods are a part of life for over a billion people across the world. However, it has been shown that menstruators are made to feel like periods are less of a bodily function and more of an embarrassing condition.

A poll by Thinx found that 58% of women have felt a sense of embarrassment because they were on their period, and that 42% of women had been shamed for their period. This may prevent those struggling from asking for the help they need.

On campus, there are various resources available for students struggling with period poverty. The school uses a program through Project Period called Givt, which seeks to provide students with pads in schools if needed.

“We got these (pads) through the health care district,” School Nurse Kate MacIntosh said. “So we do have plenty, not enough to stock the whole school, but if you have an accident and you need it, it’s here.”

In an attempt to lessen the issue on campus, students are creating initiatives and clubs, such as The Period Project and Fostering Feminine, to raise awareness about period poverty.

“The goal of our club (Fostering Feminine club) is to spread awareness about period poverty and to help raise money for women in need of basic things, such as tampons or pads,” vocal junior and Co-Vice President of Fostering Feminine club Lisa Simmons said.

Although the issue of period poverty affects many, there are ways to help.

“I think joining an organization or even just going to one volunteer drive or event really does make a difference,” Kapow said. “Donating a box of pads or tampons to a women’s shelter also helps.”

If you would like to learn about period poverty or help with this issue, join the on-campus initiatives including The Period Project and Fostering Feminine or go to projectperiod.org for more info.

![[BRIEF] The Muse recognized as NSPA Online Pacemaker Finalist](https://www.themuseatdreyfoos.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/IMG_2942.jpeg)