Huge cardboard boxes filled with keyboards containing missing letters, broken MacBooks, and frayed wires that peek out of the sides sit in the basement of Building 2. Projectors that are stacked upon each other take up multiple shelves of space, and outdated desktops line the top shelves of offices and labs in the media center.

Electronic waste, or e-waste, is comprised of electronic devices that are thrown out due to being broken, obsolete, or unwanted. E-waste can pile up in a school setting due to all of the technology that is used on campus to teach students, including Chromebooks, Smartboards, and projectors. As a school of the arts, there is extra technology that the students at this school use specifically to produce their art, such as CTE laptops, film cameras, microphones, and MacBooks. When all of this e-waste accumulates on campus, it can become a problem for students and staff alike, as they are dealing with technological clutter and the removal process.

“People don’t realize how big of an issue it is, because when you normally think of waste, you think of the normal things we recycle like paper, metal cans, plastic, or the food waste in the cafeteria, but we don’t think about how many electronics we’re using at the school,” communications junior Bianca Zapatier said. “And then we change them out every year and they break or there are chargers that break and there’s so many electronics that build up, so it’s a big problem for the school.”

All of the technologies at the school are assets of the School District of Palm Beach County, so they all have to be disposed of through a specific process mandated by the district. Technologies that have district tags on them, including computers, speakers, and document cameras, have to have their tag number removed from the school’s inventory list and taken out of the district’s system to be designated as e-waste. The e-waste is then put into large cardboard boxes and stored in the basement of Building 2 until someone from the district, or from the recycling company that the district employs, comes to pick up the boxes.

“(The boxes we use) are called Gaylord boxes, which are 10 times bigger than this cardboard box,” technology specialist Edward Maniaci said, referring to a cardboard box as tall as his desk filled with old, broken laptops and chargers. “But the two boxes I have in the basement are full, so I have to actually request more.”

Mr. Maniaci determines when the school discards the e-waste on campus by filling out a form that gets sent to someone who handles e-waste at the district level, who would then schedule the appointment for the removal. Mr. Maniaci usually requests to dispose of the campus’ e-waste twice a year, but between scheduled disposals, a lot of old or broken technology still accumulates.

“A lot can happen in six months, five months, whatever it is,” Mr. Maniaci said. “Sometimes I miss a year. Time sneaks away, and that’s what happened last year. I didn’t have a chance to (get a removal in) and now I have to play catch up, so now this order (the next removal) is going to be big.”

Although the school tries to get rid of most of the e-waste on campus when they can, in order to reduce clutter and keep it out of the students’ way, Mr. Maniaci still keeps some older, working technology to have a backup plan to replace any broken technology.

“I don’t like to be a hoarder, but I like to keep some kind of safety net just in case a student knocks a monitor off a desk,” Mr. Maniaci said. “We don’t have money sometimes to replace it, so I’ve got to come in here and figure something out … I would say maybe about a third of the stuff in here (my office) could be thrown away. (But) you never know when somebody needs a monitor, or I have a whole bunch of projectors too.”

Because most of the technology at the school is used primarily by students every day, it is often worn down. According to a recent survey from The Muse, 25% of students had broken their laptops between one to three times throughout their time in high school, including cracked screens, broken keys, and other issues.

“There’s the life cycle of a particular (technology) item, and then add to the fact that it’s in a school setting, so it’s getting used really hard,” media specialist Edward Hornyak said. “It’s not like (how) I baby my printer at home. It (the school’s technology) is getting used a zillion times harder.”

On top of electronics breaking due to mishandling, old technology becomes outdated and at times unusable when new technology comes out, contributing to e-waste buildup. As Mr. Hornyak puts it, “whenever more stuff comes in, the same amount of stuff doesn’t go out, so we end up with a surplus.”

“In the district, we have a standard Chromebook,” Mr. Hornyak said. “If it meets the standards, it can stay in rotation (and it) can be assigned. If it’s too old, it becomes obsolete. We’re not allowed to issue it and, in fact, we can’t upgrade it anymore, so it can’t be used anymore. We already have Chromebooks that have gone out of standard.”

When technology supplied to schools by the district, such as Chromebooks, CTE laptops, and Smartboards, get broken, it’s not up to schools to decide if they are worth fixing or not.

“There’s a triage of how things get repaired,” Mr. Hornyak said. “If it’s minor, it could be just like, ‘Okay, I need to take the software off this computer and put it back on.’ Sometimes that’s something we can do in-house. But if it’s a screen or a keyboard, we used to be able to do some of that stuff years ago, but not anymore. The district has to determine whether or not it’s practical monetarily to fix the item or just replace the items.”

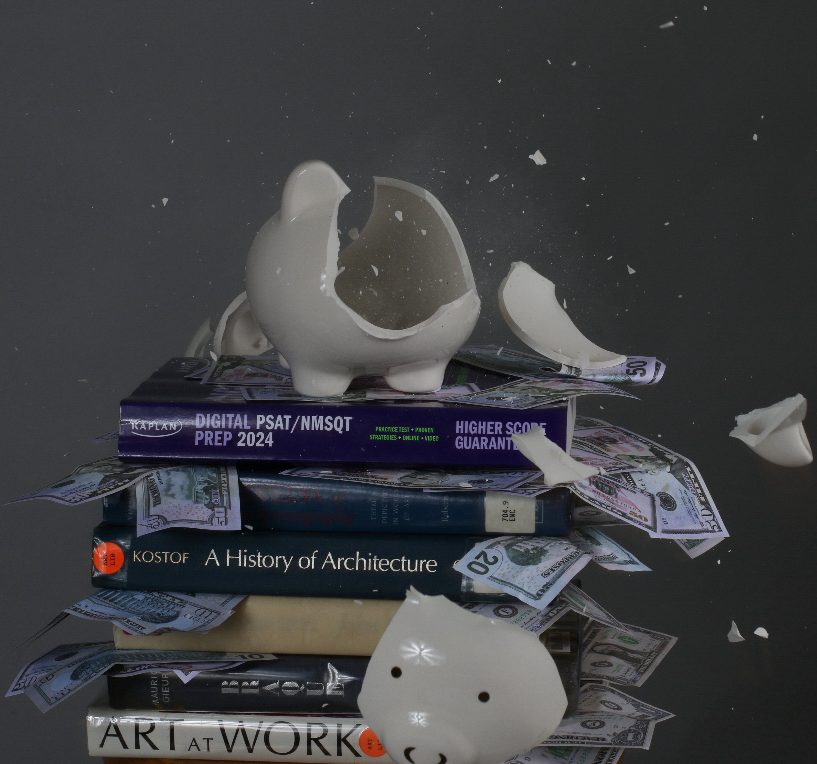

Sometimes, even when devices are fixable, it’s not worth the price to fix them by district standards. If a repair for a broken device costs more than half of the worth of the device itself, the device will instead be replaced.

“The laptop I use, let’s just say the motherboard (the circuit board that connects all of the hardware in the computer) went and it doesn’t turn on anymore. I already guarantee that’s a repair that would cost more than half what the device is worth,” Mr. Maniaci said. “I know this was a $1,500 laptop when we got it, but with the depreciation value every year, the value (has gone) down to about $750. A motherboard repair on this would be anywhere from $400 to $500. So the district’s not going to pay that. They’re just going to tell me to dispose (of) the asset … Printers’ toner gets too expensive to purchase, they get disposed of the same way.”

In addition to all of the usual devices typically provided for schools by the district, art areas also use specific technology to produce art, such as CTEs, film cameras, and microphones. This only adds to the amount of technology the school uses, and ultimately abandons, when it breaks or becomes obsolete, leading to even more e-waste.

“Well, since I got here, we started getting newer equipment, but it (all of the old equipment) is still here, and it’s shoved in storage and in closets,” TV production teacher Joseph Raicovich said. “If we take a piece of technology out of rotation, we just put it in our little storage unit here. There’s definitely some stuff that we’ll never use again, or just stuff that’s damaged beyond repair. That stuff would be really nice to totally get rid of. Other stuff that’s either old or outdated or, there was a lot of stuff that I walked into when I started working here that was from when I was a student, that is just sitting now in storage.”

When e-waste lies around, Mr. Maniaci feels it can get in the way of student activities and creates “clutter” around campus, especially in places like the media center, where there is already a lot of technology.

“It (broken technology) can make things a lot less efficient at the school, like if you want to try to finish an assignment or want to try to do something that requires technology and it doesn’t work,” piano sophomore Anthony Stan said. “Obviously, you’re going to have to spend time trying to fix it or trying to look for something else that does work, so just keeping it out of the way of students is helpful.”

According to the Global E-waste Statistics Partnership, e-waste volumes have grown by 21% in the five years leading up to 2019. Although the digital age has recently increased the e-waste problem, e-waste has been a problem for generations, with schools using electronics to teach students since the age of radios, classroom TVs, and projectors.

“E-waste is a huge problem because of growing technology,” Zapatier said. “We’re seeing a shift from traditional paper work or standardized tests to it being digital. So that just shows how much more this country and especially the state of Florida is shifting over to digital work and technology. It’s just going to become more and more of a problem, and we don’t even really think about it.”

The data included was gathered from a casual survey from The Muse that was given through a Google Form via English classes Nov. 8 and 9 to 919 students.

![[BRIEF] The Muse recognized as NSPA Online Pacemaker Finalist](https://www.themuseatdreyfoos.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/IMG_2942.jpeg)