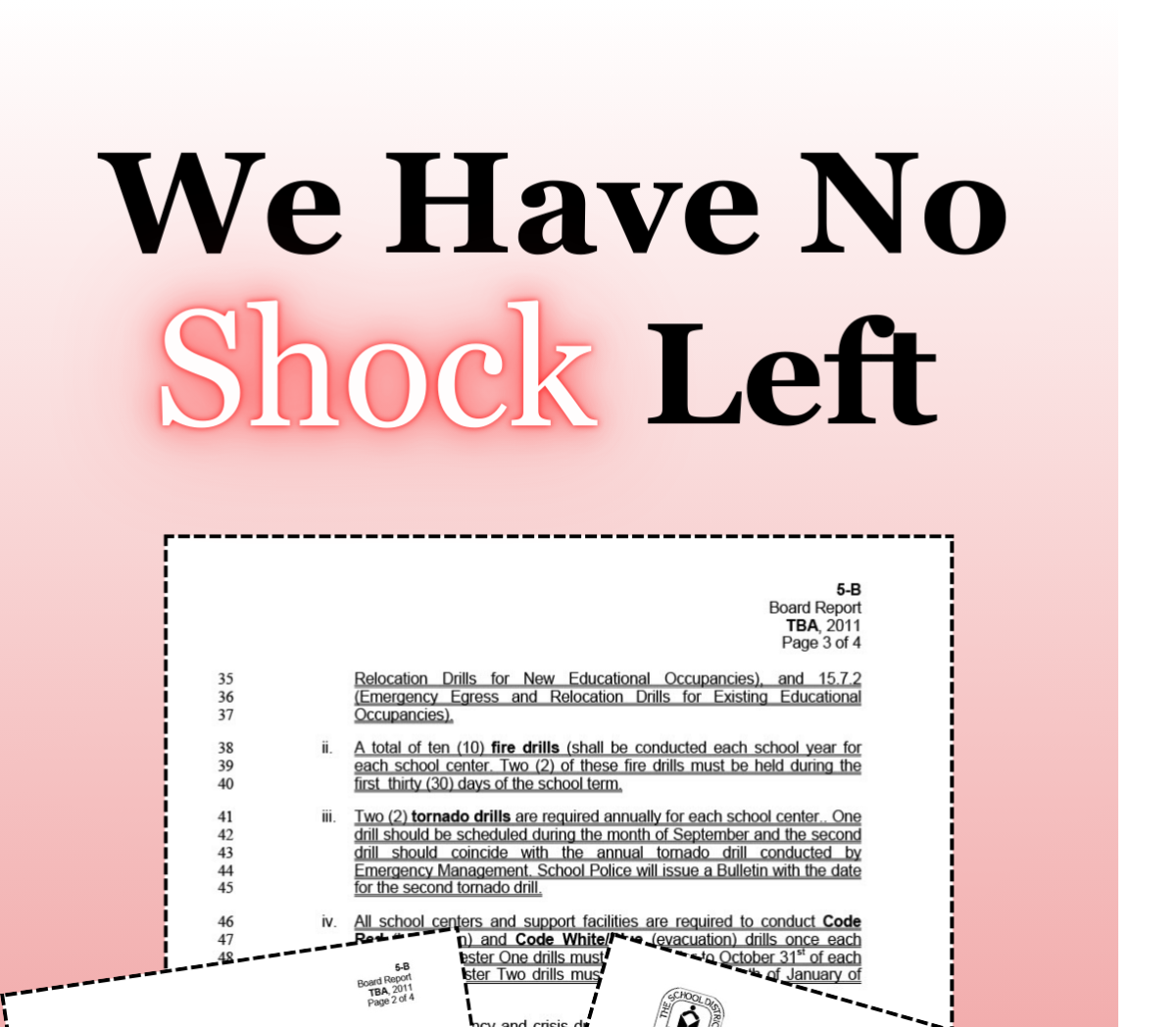

It’s not difficult to make the argument that the educational standards of the United States are becoming less and less effective. Other developed nations have consistently performed better in basic subjects such as math, reading and science. The effect is a better-prepared workforce in these other countries. It’s not simple, however, to determine the root of this problem. The real issue could be a lack of motivation in students. According to a series of reports published by the Center of Education Policy at the George Washington University this past May, nearly half of all American high school students are “chronically disengaged from school.” Making space education a bigger part of the national curriculum could help turn this around.

Changes to educational policy in the past couple of decades have been focused solely on raising test scores and achieving benchmarks. The main approach has been to give students more and more knowledge, but not necessarily to kindle awe and drive within them. Instilling the motivation to study is not easy. But including a subject that children will undoubtedly be interested in could be one way to do so. Space is something that children can easily visualize; oddly enough, faraway galaxies are much more familiar than variables in equations or elements on a periodic table. Kids getting excited about the mechanisms of rockets or the mysteries of black holes may be scientific inquiry—but in essence that curiosity is key to building interests, and in turn motivation.

As a central example, the advent of space exploration in the late 20th century inspired a generation of awestruck children and artists: beyond the effects of NASA’s programs on the STEM fields, the excitement around space produced landmark achievements in literature, film, architecture and television. Pop culture owes much to the “Star Wars” and “Star Trek” franchises, and the fiction of Stanislaw Lem and Isaac Asimov is widely read, even to this day. Despite the pervading influence of science fiction in mainstream and children’s media, there are seemingly no incentives for supporting space exploration in the eyes of lawmakers. Squabbles over the politics of public education and budgeting for NASA have hindered efforts for exploration in and out of schools that have coincided with a deficit of scientific curiosity across the country.

However, the instance of inspiring scientific exploration as based on a challenge to meet a deficit is not entirely foreign or removed. When the space program was first introduced during the Kennedy administration, the catalyzing idea was challenging the limits of innovation and creativity in the field of space exploration being set by the Soviet Union. The subsequent “Space Race,” produced JFK’s famous “We choose to go to the Moon” speech, and discoveries which would later translate into personal computers, GPS systems, and advanced calculators. What began as a duel between nations eventually evolved into an educational opportunity unlike any other: the scientific curriculum was given a significant boost, and the national incentive to form a more technologically advanced future increased. If the idea of learning about space motivated an entire country to want to study once, it could certainly do it again.

Beyond this, there is a point to be made of a larger picture: while every kindergartner, when asked to recount the events of 1492, can’t readily describe the conquest of Granada or Habsburg politics in the Holy Roman Empire,they know, and endearingly remind us that Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue. If this movement can foster support and reach implementation, could our next New World exploration take us to galaxy SXDF-NB1006-2?