When I was 13, my father caught me sneaking spritzes of his favorite cologne. He was quick to stash his prized bottle of Yves Saint Laurent Pour Homme. I was dejected; to me, the cologne’s citrus and lavender notes exuded a Parisian cool, not unlike Jean-Pierre Melville in the ‘60s classic “Le Samouraï.” But to my dad, they represented his marriage to my mother and the memories they cultivated together.

I realized then that I needed a signature scent of my own, complete with its own set of eventual, Proustian memories. I wanted something distinctive from the usual arsenal in a 13-year-old’s bathroom closet—Axe, Old Spice and Abercrombie—and figured the only way to get a product similar to my dad’s cologne was to simply make it myself.

Thus began my experimentation in the field of perfumery. Experimentation is perhaps the most appropriate term for my exploits, as is perfumery but the most fashionable of chemistries?

I had received a perfumery kit as a gift from my grandfather, a respected perfumist from São Paulo. He was a dazzling alchemist whose fingers crackled with virtuosity. But he lived a whole hemisphere away, absorbed in his work. Without his guidance, I had to learn on my own through trial and error.

When he handed me the set, my grandfather noted that it could take me years to refine my senses as a perfumist. If a musician develops relative pitch through constant ear training and a writer sharpens his craft through constant reading and revision, then a perfumist learns through constant sniffing and practicing. After excursions to Macy’s and Nordstrom, I would spend hours locked in my room, gingerly filtering through bottles of colorful essential oils and trying to memorize each one’s contents.

My first attempts were abject failures. My homemade version of an Yves Saint Laurent Pour Homme-caliber cologne instead resembled lemon Pledge. Undeterred, I made a few more batches with some improvement and even more failures, before I decided to turn my attention to perfumes.

I figured that maybe a scent for the opposite sex would yield something unlike an air freshener. Predictably, I was wrong. In perfumery, the most important (and in my “workshop,” the most ignored) rule is to keep the composition simple. Correcting mistakes with more ingredients simply convoluted the solutions, and my penchant for citrus scents only intensified the aerosol spray smells I always ended up with.

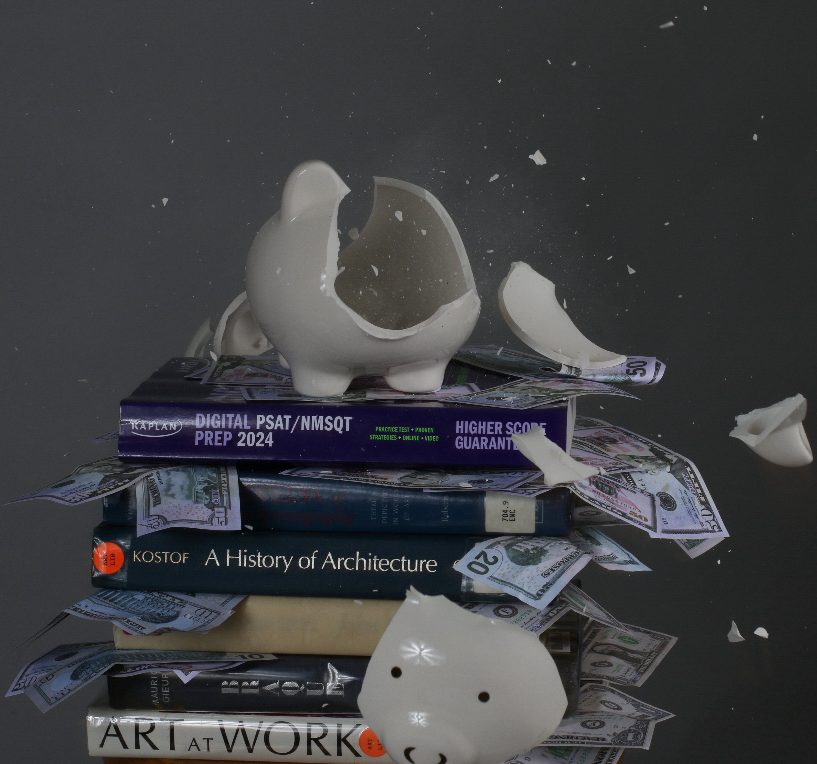

After my trial runs, I admitted that perhaps perfumery wasn’t for me. I sporadically kept up with perfumery, though. It was a fun and quirky little hobby, but one that proved too time-consuming and expensive in the long run. Last year, however, in attempting to recreate the most famous scent in all of fashion—Chanel No. 5—I surprised myself by producing a perfume that was actually not bad. I invoked both Coco and her (alleged) boyfriend, Igor Stravinsky in producing a balanced and tasteful composition of floral and citrusy notes. Perhaps I’m giving myself too much credit, but that perfume was surely closer to Chanel’s bestseller, as opposed to my Eau de Air Freshener series.

My creation—let’s call it Bomeny No. 5—was my first artistic triumph as a perfumist. However, perfumery is only an art so much as it is a science. In that regard, I failed as a scientist by forgetting to record my data. Until I cook up something good again, it looks like I’ll just be a perfumery one-hit wonder. Meanwhile, the lost recipe for Bomeny No. 5 will always remain hidden somewhere within the recesses of my olfactory cortex.