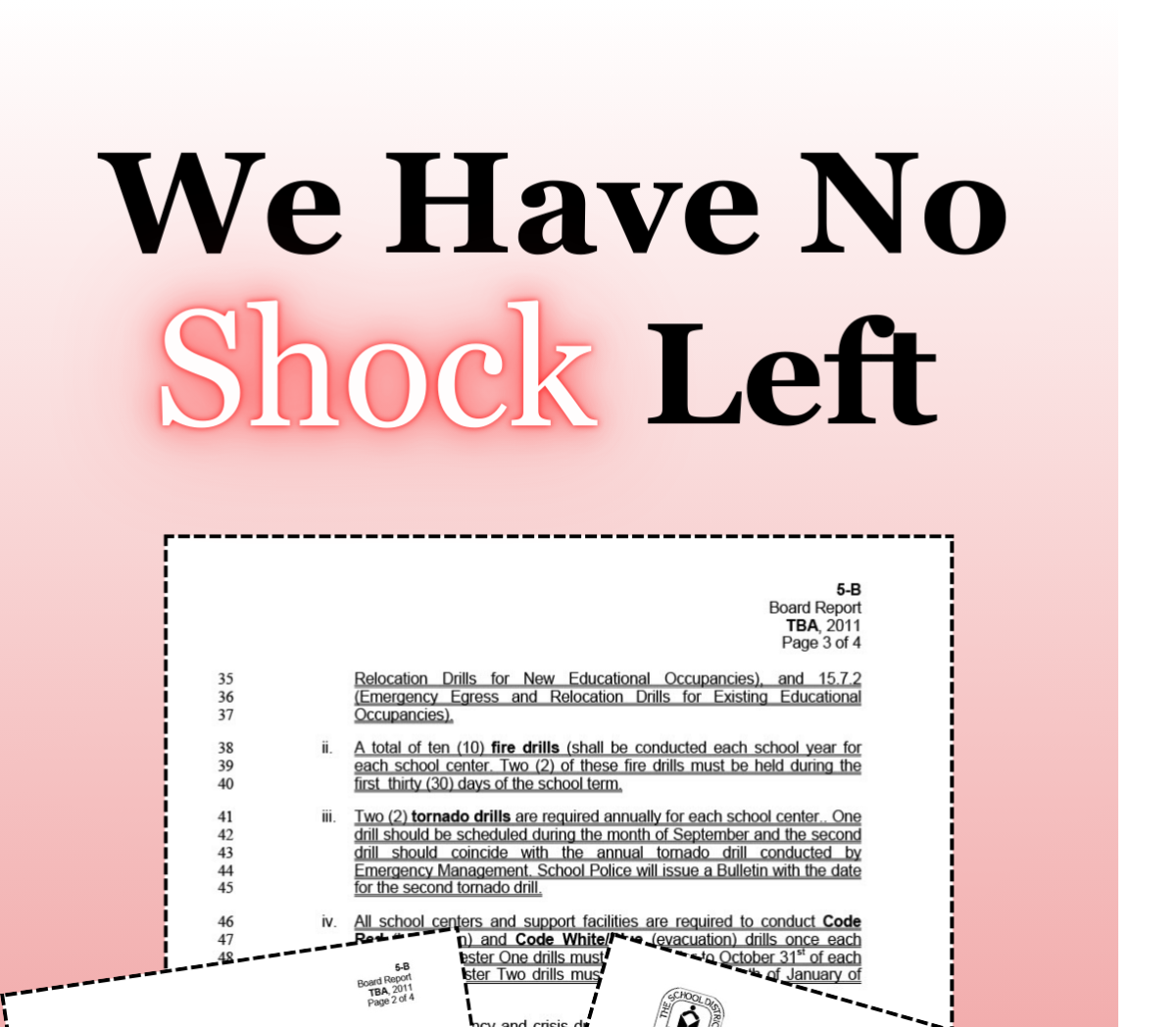

Following the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas Community High School that claimed 17 lives, students at the school and across the country organized protests, contacted legislators, and penned op-eds calling for gun reform. Despite the immensity of their movement, few of these students could demand action in the place that mattered most: the ballot box.

In recent years, student activism has spurred some individuals and organizations to seriously consider the arguments for lowering the minimum voting age from 18 to 16. Nancy Pelosi and most of her Democratic colleagues in the House of Representatives have come out in support of the idea.

Why do 16 and 17-year olds want to vote? The simple answer happens to be the reason most other Americans are civically engaged: to show off their moral superiority with “I Voted” stickers.

The more relevant question is, “Should juniors in high school have the ability to select their elected officials?” The answer to that is even more simple: yes.

Teenagers are Dumb, but so are Old People

It may seem irresponsible to allow the generation that ate Tide Pods for fun have a part in electing their leaders in government, but classifying all teens as Tide Pod-eating dimwits is a broad generalization of a diverse group that, surprisingly, includes some moderately intelligent people.

It may also seem like a bad idea to allow the 75 percent of Americans who can’t name the three branches of government to vote, but we do it anyway. So if you know one of the most basic facts about American government, congratulations, I guess. (The branches are legislative, executive, and judicial, by the way. If you didn’t know that, stop reading this and pick up a middle school civics book.)

When it comes to politics, 16 and 17-year-olds are just as knowledgeable as 18-year-olds who can already vote. “But wait!” you say, “I heard that teenagers’ brains aren’t fully developed or something like that.” Thank you for the compliment.

That statement is true, but misleading in this situation. While some areas of the brain associated with decision-making aren’t completely developed until one’s early 20s, those parts are mostly associated with what is called “hot cognition,” which is involved in spur-of-the-moment, emotional decisions when there’s little time to think logically.

That’s part of the reason why teenagers are often motivated to do dangerous or questionable things for the entertainment or approval of their friends (like eating Tide Pods). It’s also an argument for raising the minimum age to purchase firearms to 21.

“Cold cognition,” on the other hand, is nearly fully developed by the time one turns 15. Cold cognitive abilities are used in calmer situations when people have time to analyze a decision and weigh the advantages and disadvantages of different options. Selecting a candidate to vote for would (hopefully) fall under the realm of cold cognition.

And for the record, it’s not our voting decisions you should be worried about. At 70 years old, a person’s hot and cold cognitive abilities are almost as bad as an 8-year-old’s. Now that you know, go look up how old the president is.

So, our brains seem to be up to the task of voting, but would 16-year-olds actually care enough to do it?

Make America Vote Again

Young Americans are notoriously bad at showing up to vote. Only 35 percent of eligible voters aged 18–29 actually cast a ballot in the 2018 midterm elections, which is somehow monumental in comparison to the abysmal 20 percent of voters in the same age group who turned out in the 2014 elections.

The data for presidential elections isn’t much better. In 2016, less than half of the youngest voters could bring themselves to “Pokémon Go to the polls,” despite Hillary Clinton’s inspirational call to action.

Many would assume the same would hold true for 16 and 17-year-olds who had the ability to vote, but the opposite seems to be the case: Not only would these newly enfranchised teenagers vote at higher rates than current young voters, they would continue to do so for the rest of their lives.

Several countries already set the voting age at 16, including Argentina, Ecuador, Scotland, and Austria. A few cities in the U.S. have followed suit, the first of which was Takoma Park, Maryland.

When Takoma Park changed its voting age in 2013, 16 and 17-year olds voted at quadruple the rate of other cohorts and voted at even higher rates in the local elections two years later. That’s a shocking statistic, especially in the context of young voters’ low national turnout.

Why did the youth of Takoma Park vote in such large numbers? Before we can answer that, it’s important to understand the trends and circumstances that impact one’s likelihood to vote.

One of the biggest indicators that someone will vote in an upcoming election is a consistent record of voting in previous elections; one analysis of polling data showed that the odds of one person voting are raised by 25 percent if that person has voted at least once before.

That’s because, as hundreds of studies confirm, voting is a habit. When voters skip their first elections, they fail to build that habit and may instead perpetuate a cycle of civic indifference. As a result, a huge chunk of the American electorate is not politically involved and may not have their problems solved.

The current voting age of 18 makes it difficult for citizens to actually start voting and make a habit of it. At that age, most students are starting life in college, where they are living on their own, often in an unfamiliar place with new politicians to learn about or even different political offices to vote for.

Having the legal right to vote at 16, however, means that students can begin voting in a more familiar setting, where they won’t have to do as much research about local and state politics on top of collegiate responsibilities and full-time jobs. They can also receive encouragement to engage in the political process from their families, friends, and schools. Lowering barriers to voting for the first time can also lower the barriers to voting the next time.

Wouldn’t this Make America a Barren Land of Filthy Communists?

“That’s great,” you say, “But I’m not fully convinced that a 16-year-old would be capable of voting for the things that actually matter. They might vote a lot, and they might make their choices carefully, but I just don’t think their goals could ever match up with what’s best for the country. Wouldn’t they just want free stuff? They’re not even paying into the system!”

It is true that we love free stuff, which is why Costco’s endless array of free samples always fills me with indescribable joy. But it’s not true that we don’t have a stake in the political process, and it’s certainly not true that we would jeopardize the national interest for short-term rewards. There are countless ways in which real policies affect real people, but the only difference between the young and the old is that we’re not allowed to have a say in shaping the laws that govern our lives.

We’re allowed to work with unlimited hours and pay income tax. We’re allowed to die in our schools as politicians do nothing. We’re allowed to sit and watch as climate change threatens the world we hold dear. We’re not allowed to have a voice.

Elections have consequences. And with every election, the problems that will most greatly affect our youngest citizens and the long-term prosperity of America are swept under the rug. Without enough young constituents to hold politicians accountable, the deficit continues to climb, global temperatures continue to rise, and school shootings continue to be business as usual.

In addition to incentivizing politicians to address the most pressing challenges of our lifetimes, allowing younger people to have a voice in government would foster a more informed voting population. In an aging America, older people are more likely to believe and spread fake news and misinformation online, which further contributes to political polarization.

People aged 65 and older will soon make up the largest age group in the U.S., and their high voting rate coupled with their high political contributions would make the misinformed interests of the senior class play an outsized role in governance. Lowering the voting age would help to offset some of the influence that fake news has in the public arena, while ensuring that leaders focus on solving issues that could be devastating to future generations.

And while more students use their political power in elections, classes on civics and government would become increasingly relevant. As they’re able to actually apply the knowledge they gain in a real-world scenario, students would be more likely to pay attention to new information and current events, and schools might allocate more resources to ensuring that students can be responsible voters. By allowing more people to vote, we can raise the quantity and quality of voters overall.

Change doesn’t start at the top, and it never has. From the champions of the civil rights movement to the young protesters who gave 18-year-olds the right to vote, it was the people who shaped their government and not the other way around. Even small steps, like allowing 16-year-olds to vote in local or school board elections, can bolster a greater vision. As we age into our right to vote, let’s not take that right for granted. Let’s use it.

![[BRIEF] The Muse recognized as NSPA Online Pacemaker Finalist](https://www.themuseatdreyfoos.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/IMG_2942.jpeg)