A Preamble

I am a proud, patriotic American. A shrine to George Washington sits in the corner of my room, each of my 13 bald eagles remains groomed to perfection, and every inch of my body is tattooed red, white, and blue (painful, but worth it).

When Thomas Jefferson declared that “all men are created equal, [except slaves because they don’t count apparently],” he set forth an idea so powerful that it continues to shape modern American ideals. Recently, students were made to recite this exact passage on each day of Dreyfoos’ Freedom Week.

Although I remain completely dedicated to my country, my patriotic sentiments compel me to point out that one policy of the Palm Beach County School District seems to directly conflict with the notion that students are equally valued as individuals. I speak, of course, of the class rank system. This attempt to place students on a quantified hierarchy based on a questionable measurement of academic achievement degrades not only the students near the bottom of that hierarchy, but also those near its peak. Now is the time to apply the American ideal of equality that we claim to value so highly by doing away with a system that explicitly shuns that very concept.

Life, Liberty, and Learning

Thomas R. Guskey, professor of educational philosophy at the University of Kentucky, posits that “educators face one basic question about their purpose … Is my purpose to select talent, or is my purpose to develop talent? The answer must be one or the other because there is no in-between.”

Ideally, developing talent would be the sole focus of teachers and administrators. Ideally, the education system would encourage students to learn as much as possible, even in subjects in which they lack prior knowledge or innate ability. Ideally, students would pursue that learning with passion.

We do not live in an ideal world. We live in a world of misery, despair, and gloom (although Spider-Man is back in the MCU, so there remain a few glimmers of hope). The class rank system emphasizes the differences in students’ abilities rather than seeking to raise those abilities to their highest potential. Instead of developing talent, the school district seems intent on selecting it.

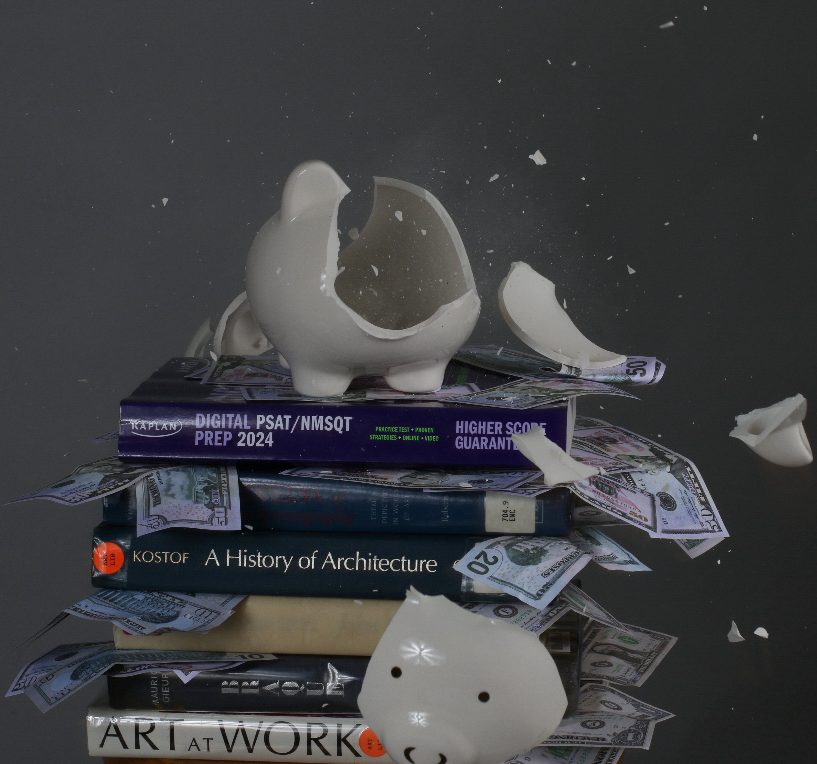

That selection process takes its toll on all who endure it. Because many students seem to perceive class rank as a reflection of their worth, intelligence, or potential for success, trivial differences in HPA can have major impacts on their mental well-being. Based on a survey conducted last year by The Muse, 59 percent of students report feelings of discouragement, unhappiness, or inferiority because of their class rank.

This is despite the fact that subject proficiency in reading and math at Dreyfoos is nearly double that of the state and district averages; despite the fact that while 71 percent of Dreyfoos seniors last year had taken seven or more AP or AICE classes throughout high school, only about 28 percent of American high school graduates have taken a single AP test*; and despite the fact that people like me wave these facts around pretentiously. It’s difficult to view academic success as academic success when students are constantly reminded of their failure to be quite as “successful” as their peers, even if the rest of the world would consider them exceptional students.

“But wait,” you say. “I just had a clever thought. Doesn’t class ranking encourage students to become even more exceptional?” Lucky for you, I anticipated your clever thought and am here to provide you with the truth. If you consider educational success to be a high HPA, then perhaps you have a point. The students at the top of their class may find themselves motivated to take Underwater Basket Weaving 101 as a dual enrollment credit to boost their decimal by a few hundredths. But if you consider educational success to be actual learning, then class rank is a major obstacle to that pursuit.

Of the students surveyed last year by The Muse, 56 percent “strongly agree” that, “in general, Dreyfoos students care more about grades than learning” (32 percent merely “agree”). Sixty percent said cheating can be worth it. Seven percent—nearly 100 students—admitted to using Adderall or a similar drug before a test. It’s clear that class rank contributes to a culture in which students forfeit knowledge for a number. Rather than taking classes that appear interesting and seeking to master content, class rank rewards students who cheat, sacrifice their sanity, and take the easiest classes for the most credit.

But most of that only applies to students ranked in the upper half of their class. For those with lower class rankings, the system can have the opposite effect. Alfie Kohn, author of books like “The Schools Our Children Deserve” and “No Contest: The Case Against Competition,” argues that, “If the chance to be a valedictorian is supposed to be a motivator, then the effect of class rank is to demotivate the vast swath of students who realize early on that they don’t stand a chance of acquiring this distinction.” While the most competitive students suffer from unrealistic expectations, students incapable of playing the HPA game suffer from a defeatism that causes them to give up on challenging learning. Either way, the message that our class rank system sends—that grades and highly weighted classes matter more than intellectual curiosity—limits learning for nearly every student.

A Word on Colleges

At this point, some mother may be sitting at home with her hand over her heart, exclaiming, “Oh dear! But how will my little Timmy make it into Yale without being valedictorian?” Have no fear: Timmy can still go to Yale without class rank. And if you’re that concerned about it, please consider the fact that getting into a top college isn’t quite as important as you might think, and your high expectations for your children could end up backfiring in terms of their overall happiness.

I digress. The point is that class rank isn’t necessary to acquiring a good college education or developing a successful career. In fact, 63 percent of colleges find class rank to be of limited or no importance in determining an applicant’s admission status. This may be at least partly because about half of schools no longer report class rank to colleges. At Dartmouth College, only a third of the Class of 2018 came from schools that reported class rank.

Many still believe that ranking students is useful in evaluating their academic performance in the context of their school. Once again, this argument comes with the premise that high schools ought to focus on selecting talent over developing it, essentially performing the job of college admissions officers for them.

And while class rank may provide context for a student’s HPA relative to those in their school, it fails to accurately measure a student’s actual learning and character. Those attributes are better evaluated by a more holistic review of college applicants that seeks to determine a student’s interests, skills, and unique experiences without relying on a flawed ranking to do so. The elimination of class rank from many high schools has encouraged admissions officers to view students less as numbers and more as people.

But even if class rank were a valid measurement of learning and education and even if its absence did stop Timmy from getting into Yale, would it still be worth it if keeping class rank also meant maintaining a culture of toxic competitiveness, stress, and ignorance? If we want to build a school environment constructive to learning and happiness, then we need to recognize what’s wrong with our current approach to education and fix it.

A New Revolution

This morning, as I knelt before my George Washington shrine, I thought about how he had helped a tiny group of colonies win a seemingly unwinnable war against the world’s largest military superpower. Surely, I thought, if we can declare independence from an oppressive government, then we can do the same from an oppressive educational practice.

Class rank is antithetical to the American ideal of equality—George Washington told me so. But it’s also antithetical to the goals of education. The leaders and administrators of our school system have the power to change a system that doesn’t work, and we have the power to tell them so. It’s a crazy thought, but if we stop pitting students against one another, maybe we can start building each other up. If we shift our goals from selecting talent to developing it, maybe we can discover the love of learning again. And if we embrace students as more than just digits on a screen, maybe they’ll see themselves that way too.

*This figure was derived by dividing the total number of 2012 U.S. public high school graduates who had taken at least one AP exam by the estimated number of graduating seniors in the U.S. from SY11-12.