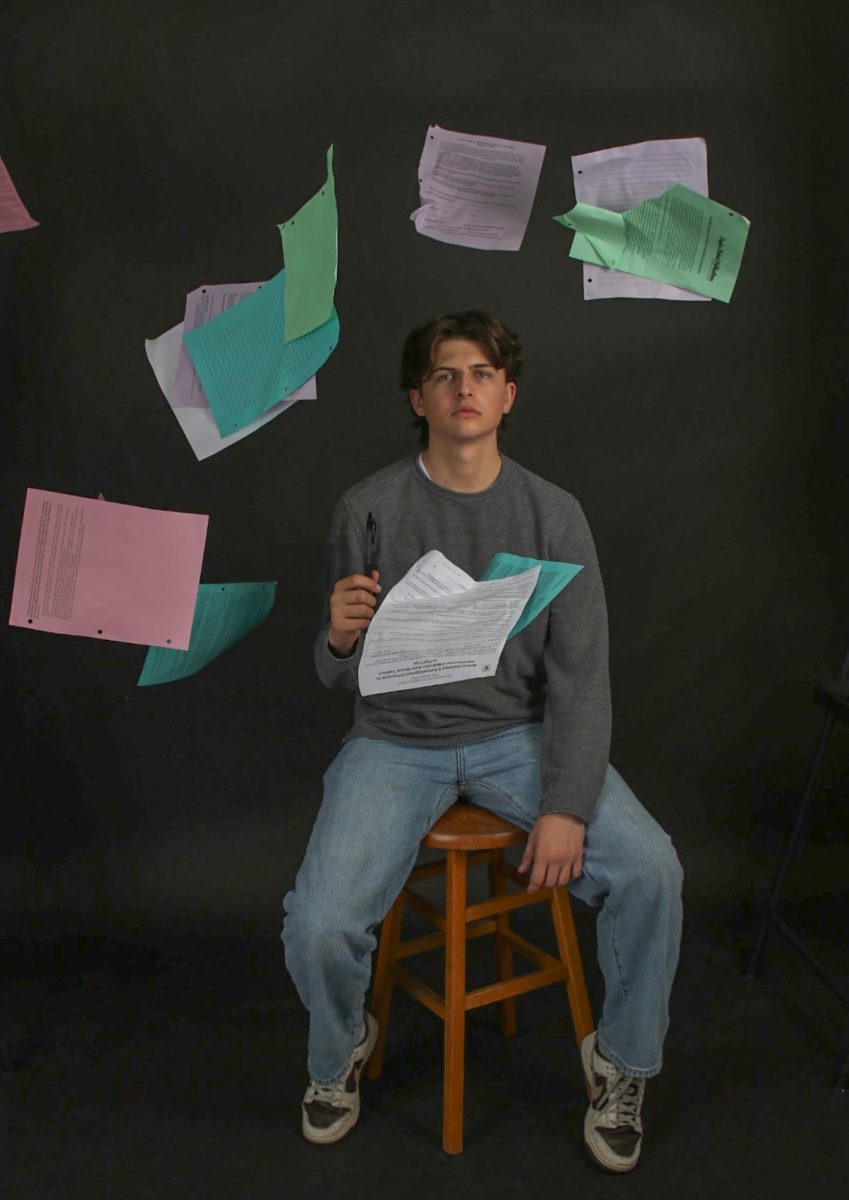

When we said we needed gun reform, what the state legislature heard was, “Set up a mass surveillance system in our schools.”

As part of Florida’s efforts to prevent school shootings since the Parkland massacre last year, the state has, in fairness, significantly improved its relatively lax gun laws (although, I would argue, we still have much left to do). That made sense. What didn’t, though, was the creation of a centralized database loaded with students’ personal information.

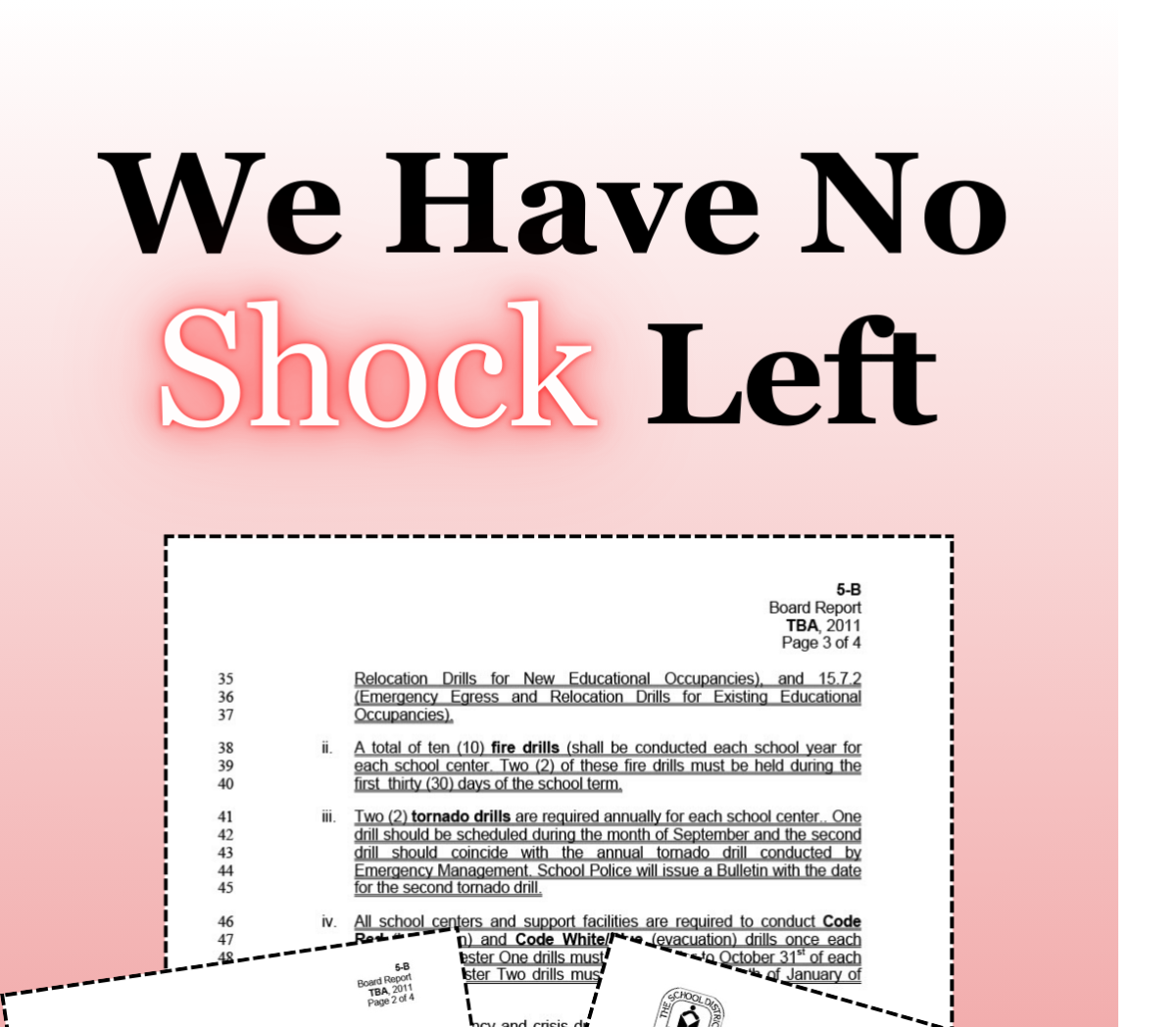

The Florida Schools Safety Portal (FSSP), established on Aug. 1, 2019, was developed to “identify, assess, and provide intervention services for individuals whose behavior may pose a threat to themselves or others,” in the words of a Florida Department of Education press briefing. It’s accessible to each school’s “threat assessment team” (typically comprised of school resource officers, guidance counselors, and administrators) and contains information on each student that will supposedly help in stopping school shooters before they strike.

What data makes it into the FSSP? If, for whatever reason, you’re reading this out loud, I would advise you to take a deep breath before the next sentence. The portal contains “thousands of hours of video footage, grade cards, student disciplinary records and teacher memos … ‘information on children collected through social media monitoring, local law enforcement agencies, the Florida Department of Children and Families, Florida Department of Juvenile Justice, Florida Department of Law Enforcement, Baker Act admissions, [FortifyFL], and the School Environmental Safety Incident Reporting System.’”

With all that personal data, it’s easy to see why 33 advocacy groups, including the ACLU and the Southern Poverty Law Center, expressed concern to Gov. Ron DeSantis over the FSSP’s use as a “massive surveillance effort.” The broad power of the government and school officials to monitor students’ social media accounts with “unlimited keyword searches” and location tags is deeply unnerving. What could mandate such disturbing intrusions on children’s intimate information without their consent? School safety, says the Governor.

In the last two decades, many of our nation’s bravest trees have given their lives to print thousands of books, editorials, and newspaper columns on the issue of “privacy vs. security.” But the FSSP fails to promote either ideal.

As education technology researcher Ora Tanner pointed out, “There just isn’t enough information about the small number of students who actually commit mass acts of violence, compared to data about students who make up the entire school population … Any conclusions drawn from an analysis of the data will be unreliable at best.”

In other words, it’s unclear how hoarding a sixth grader’s private information could be at all useful in preventing a shooting at her school when we still haven’t accurately assessed the distinct characteristics of school shooters. When the FBI released a threat assessment on school shooters in 2000, the introduction carried a stern disclaimer in bold and italics: “This model is not a ‘profile’ of the school shooter or a checklist of danger signs pointing to the next adolescent who will bring lethal violence to a school. Those things do not exist.”

Recent studies support the idea that school shooters rarely conform to patterns of behavior that clearly indicate their intentions to cause harm (with the probable exception of direct threats and leakage of plans). So, it’s difficult to determine what would cause a student to commit a shooting at their school. With the introduction of the FSSP, Florida seems intent on collecting swaths of student data with no apparent scientific basis for doing so.

While little of the information in the data portal seems to hold potential for improving school safety, the FSSP could erode students’ intellectual and emotional security. In other contexts, greater government surveillance has been shown to cause more self-censorship in online speech and lower feelings of safety at school. Privacy, free speech, and emotional assuredness are too high a price for a security system that hasn’t proven itself effective.

If not invasive data collection, what would be an effective way to keep students safe?

Although there’s no definitive profile of a school shooter, there is one thing that every shooting has in common—guns. Despite important changes to Florida’s firearm regulations in recent years, critical steps remain to be taken in our efforts to stop mass shootings in schools:

- Universal gun licensing:

Gun licensing, a more rigorous process than federal background checks, is already used in 12 states and has the support of 82 percent of the American people.

For a model of an effective gun licensing system, look no further than Massachusetts: Obtaining a gun license is only possible after taking a firearm safety course and submitting an application to the local police department. After completing a thorough evaluation of criminal, mental health, and other records, police chiefs may authorize an individual’s license to carry (LTC) or firearms identification card (FID). Ninety-seven percent of applicants receive their gun license, but the broader effect of Massachusetts’ gun policy is that it reduces state gun ownership rates, which in turn lowers gun deaths. Massachusetts’ approach has been so successful that the state boasts the second-lowest rate of gun deaths in the country.

Massachusetts isn’t the only place with a success story. When Connecticut passed a gun licensing law in 1995, the state’s gun homicide rate dropped by 40 percent. On the other hand, when Missouri repealed its licensing law, the number of gun homicides spiked by 23 percent. A study of 80 urban counties reveals that county gun licensing policies reduce firearm murders by 11 percent. Although there’s no data for how gun licensing affects the number of school shootings, a lower gun ownership rate could stop would-be shooters from borrowing firearms from parents and relatives. At the very least, these promising results from across the country show that such a program couldn’t hurt.

- Assault weapon regulations:

Assault weapons, semi-automatic firearms based on military weaponry, were used in all seven of the deadliest mass shootings in the last decade. The Parkland shooting was one of them. Although assault weapons account for less than four percent of total US gun deaths, regulation is still necessary if we want to limit deaths and injuries in mass shootings.

The U.S. began enforcing a ban on assault weapons in 1994, but the law expired 10 years later and was never renewed. One recent NYU study found that when the ban was in effect, there were 70 percent fewer mass shooting fatalities. The study also concluded that 85 percent of deaths in mass shootings are caused by assault rifles.

Other research reveals that assault weapons bans, both on the federal and state levels, have been associated with 54.4 percent fewer deaths in school shootings. The numbers are clear: Regulating these deadly machines could significantly reduce the number of people killed in mass shootings.

- High-capacity magazine ban:

Like a ban on assault weapons, a ban on high-capacity ammunition magazines (defined as magazines capable of holding 10 or more rounds of ammunition) would serve to reduce deaths in mass shootings. When shooters use high-capacity magazines, they can fire more bullets in a shorter amount of time, resulting in a greater number of fatalities. Mass shootings involving large-capacity magazines kill twice as many people as those with lower-capacity magazines. Although much of this is likely also due to the types of weapons used in these mass shootings, a limited magazine capacity has already saved lives in at least one instance: During the Parkland shooting, a group of students escaped the shooter by running down a stairwell as he paused to reload his weapon.

These ideas aren’t perfect, but they’re better than the ones we have now. Until we’ve attempted every evidence-based solution to gun violence, our thoughts and prayers will never be enough. Neither will our databases.

The Muse welcomes all student opinions and encourages readers to share their thoughts on this or any other recent Muse article by submitting letters to the editor. We look forward to reading and publishing the best of what our student body has to say.

![[BRIEF] The Muse recognized as NSPA Online Pacemaker Finalist](https://www.themuseatdreyfoos.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/IMG_2942.jpeg)