AM I RIGHT OR AM I RIGHT?

THE DANGERS OF CONFIRMATION BIAS

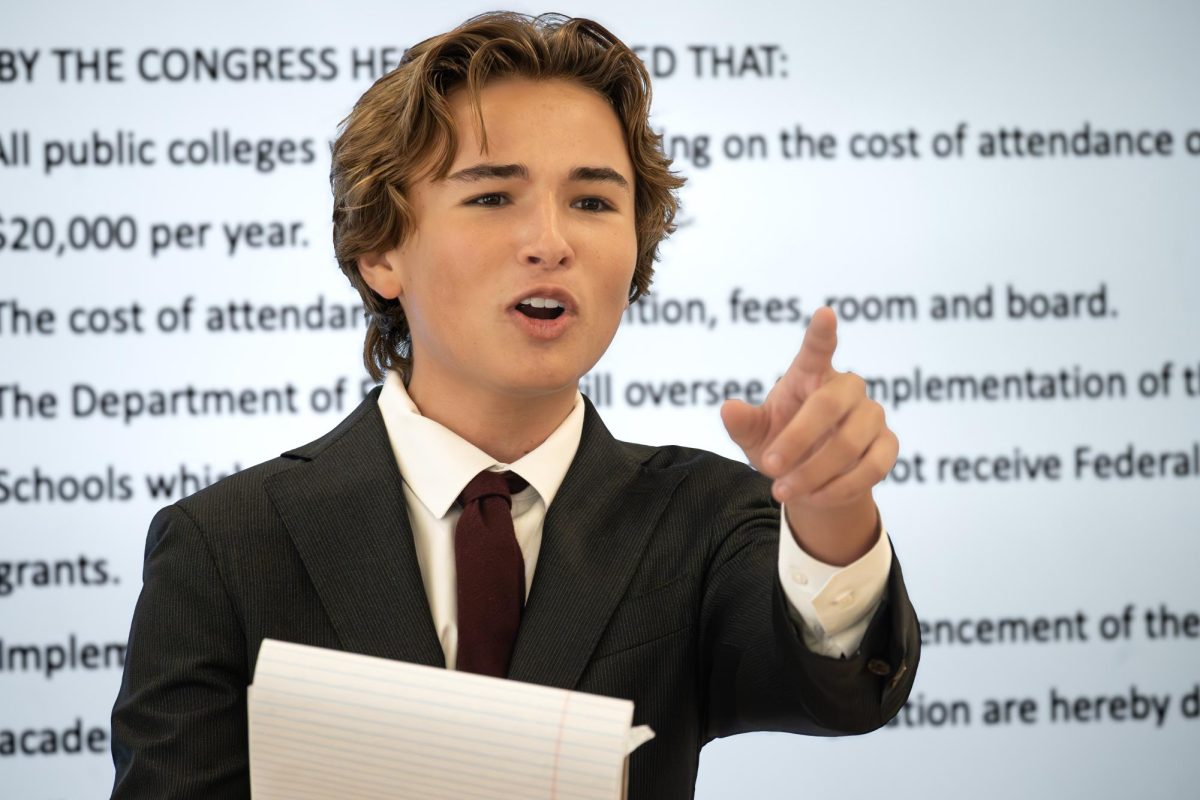

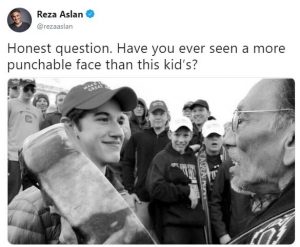

When videos first surfaced of Covington Catholic student Nick Sandmann and Omaha Tribal Leader Nathan Philips facing off, most people were quick to jump to conclusions. With the help of the media, the public became enraged by the actions of Sandmann, his fellow students and the perceived disrespect they had shown an Omaha tribal elder. The truth is that without the full scope of the issue, the internet allowed the situation to be characterized by Sandmann’s white skin and the Make America Great Again hat. He was demonized, but not solely because of his actions. Preconceived notions heavily impacted the way people viewed and discussed Sandmann’s behavior. That day in front of the Lincoln Memorial was about more than who was right or wrong; it’s also a prime example of how the growing phenomenon of confirmation bias can have real consequences for real people.

Reza Aslan, an American Scholar, is now facing a possible lawsuit for his tweets about the Sandmann-Philips confrontation in January 2019. Sandmann’s lawyer has cited the scholar as “top target” for his legal team.

Psychology Today defines “confirmation bias” as “the human tendency to seek, interpret, and remember information that confirms [their] own pre-existing beliefs.” It’s normal for people to form opinions on literally anything, even something as nominal as a football game. One experiment [conducted by Princeton University and Dartmouth University] pitted Princeton and Dartmouth students against each other in a sports game to test exactly how confirmation bias and the need to be right can affect all of us, even in the smallest ways. Once the game came to a close, researchers found that students were more likely to remember fouls committed against their own respective teams. By some people’s standards, this is just some students supporting their school’s sports, which is perfectly natural. But the truth of the matter is that this study became an example of confirmation bias the moment that students rejected information in favor of reinforcing their own opinions. Arguably, the most important discovery of the study was that “both groups of students fundamentally believed that their school was better,” regardless of the game’s outcome. The best way to distinguish between having an honest opinion and falling victim to your own bias is to assess whether or not you are willing to reject valid information just so that you can be right. It’s whether or not you’ll choose to consider the wider scope of an issue or if you’ll choose to be isolated to what you already believe.

The impacts of confirmation bias are not solely confined to sports games. In fact, at no point have the impacts of preconceived notions been on a larger display than in January 2019 in front of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C.. The image of Nathan Philips and Nick Sandmann flooded the internet, and while the story began to gain traction in the media, so did an unflattering narrative. A white boy wearing a “Make America Great Again” hat harassing a Native American man in the capital of the United States emerged as the media’s version of events. Unsurprisingly, most Trump opposers took this as the reassurance of what they already thought: Being a Trump supporter was the same thing as being a racist. In this situation, it didn’t matter if you were pro- or anti-Trump; what mattered was that a lot of people, even those at Dreyfoos, allowed this narrative to become their view of the situation. But when subsequent news reports widened the scope of the story and revealed the existence of a third party, people still chose to put the boys at fault. This third party, the Black Hebrew Israelites, had verbally harassed the boys for their beliefs and Nathan Philips thought that by stepping in, he was calming the situation down. Sandmann later released a statement that the Omaha elder’s move “startled and confused” him, rather than de-escalating the confrontation. The truth is that it’s hard to distinguish what happened that day or who was at fault. It’s entirely plausible that people who believe Sandmann was to blame are right, but it’s also plausible that there is blame to be placed on each party involved. In any case, we must dare to look a little bit deeper.

It would be blatantly incorrect to say that when people discover new information, their beliefs don’t waver at all. In a sense, people who don’t believe in the phenomenon of confirmation bias or the idea that people’s opinions have become presets are correct. Kind of. A study published in Scientific Reports found that when 40 hard-line liberals were shown evidence that directly contradicted their own beliefs, their strength in those beliefs decreased. Despite this, the important takeaway of this study is that, often, any decrease in faith occurred in less personal areas, such as nonpolitical beliefs, but the principles that meant the most to subjects saw a minimal change (stances such as abortion saw no change). It’s impossible to say that one can take directly contradictory evidence without flinching, but that’s not what confirmation bias mandates. Confirmation bias is the tendency to understand, comprehend, and then disregard any information that contradicts one’s beliefs. That is what happened when these 40 liberals were faced with the possibility of being wrong: They chose to move on from the information and continue to accept the data that supported their own conclusions.

While it is true that confirmation bias exists, and it’s probably played a key role in most of our decisions, it’s also true that there is a way to stop it. There’s a simple solution that most of us never truly consider, which is to just look deeper.

We’re living in such a connected world, filled to the brim with different beliefs and ideologies; yet, the steady flow of information has made us lazy. We’ve decided to take things at face value and to only accept what we deem to be true. Curated news feeds and social media pages fill our minds with people who only reinforce what we already think, and we use phrases like, “Am I right, or am I right?” as if they mean nothing. Yet, if we choose to do the extra research, to look into the other side of the debate, to find the unbiased source, and to keep an open mind while we do it, maybe, just maybe, we’ll find ourselves just a little bit more understanding of each other. That is what it’s like to be truly connected.

The Muse welcomes all student opinions and encourages readers to share their thoughts on this or any other recent Muse article by submitting letters to the editor. We look forward to reading and publishing the best of what our student body has to say.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Dreyfoos School of the Arts. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.