![thing Watson, left, and Inayat Sood, right, geared up and ready to go to work. At the Medical Examiner Office of Palm Beach County, Watson worked closely with those involved in the field of forensic pathology as a summer job, shadowing medical examiners in autopsies and accompanying investigators to crime scenes. “I am so grateful for the opportunity that [Dr. Wendolyn Sneed has] given me,” Watson says, reflecting on her unique job during the summer. Photo courtesy of Alex Watson’s VSCO.](https://www.themuseatdreyfoos.com/wp-content/uploads/elementor/thumbs/thing-ov0wgidiyn6xo16nf6feyo6wptozi0wvdop4ghua68.jpg)

Trigger warning: This story discusses intense details regarding h*micide, s*icide, and death. Readers sensitive to this subject matter should proceed with caution.

Alex Watson touches dead bodies.

Between studying for the SAT and chilling with friends—which comprised much of her COVID-19 summer—Watson, who wears a navy Cornell Sweater and posts her film photos on VSCO, lives a seemingly secret life helping the Medical Examiner Office “conduct investigations of violent, sudden, unexpected, and suspicious deaths” in Palm Beach County, 40 hours a week.

For someone who likes to laugh, she isn’t joking.

Watson walks through the office, which is strung with blue and white streamers, adorned with ancient-looking textbooks, and home to Phil the Dummy (a medical mannequin currently not in use). It’s where “all the morgue technicians, the investigators, the doctors come inside of the conference room. We go through all the cases that we have for the day or that happened the night before.”

As Watson explains what she does with a healthy infusion of forensic pathology jargon, I try to hold back my surprise. “Homicides, suicides, and accident[s],” according to Explore Health Careers, are all means of death that medical examiners explore during their careers. (Usually, teen summer jobs consist of Publix gigs or Delivery Dudes. Not touching dead people.)

She laughs, and agrees with the unconventionality of her job.

“I never really thought about what [Forensic Pathologists] did,” Watson said. “I was like, ‘Oh, that’s really cool. But weird.’ I mean, it’s dead people.”

For Watson, this detail is vital—her work day starts with driving to the office, attending the team meeting, and writing up Covid reports for the deaths in Palm Beach County. It’s a job that, today, provides crucial statistics that will get kids back to schools, adults to work, and life to pre-COVID-19 conditions. She puts it bluntly: “This job is really important for the county.”

However, like any job relating to deaths and uncertainties, Watson’s day-to-day work is also filled with unexpected interjections.

“If there’s a scene, the investigators will come in and be like, ‘Do you want to go to a [crime] scene?’ In that case, it’s different every day,” Watson said, recounting a story from earlier that week. “It was an older man who had shot himself while he was driving. His car went into reverse and started doing donuts around the road. A witness came and tried to smash his window open so he could stop the car, and he fell. The car ran over his arm.”

“It was pretty intense,” she said, sighing. “It was the worst thing I’ve ever seen.”

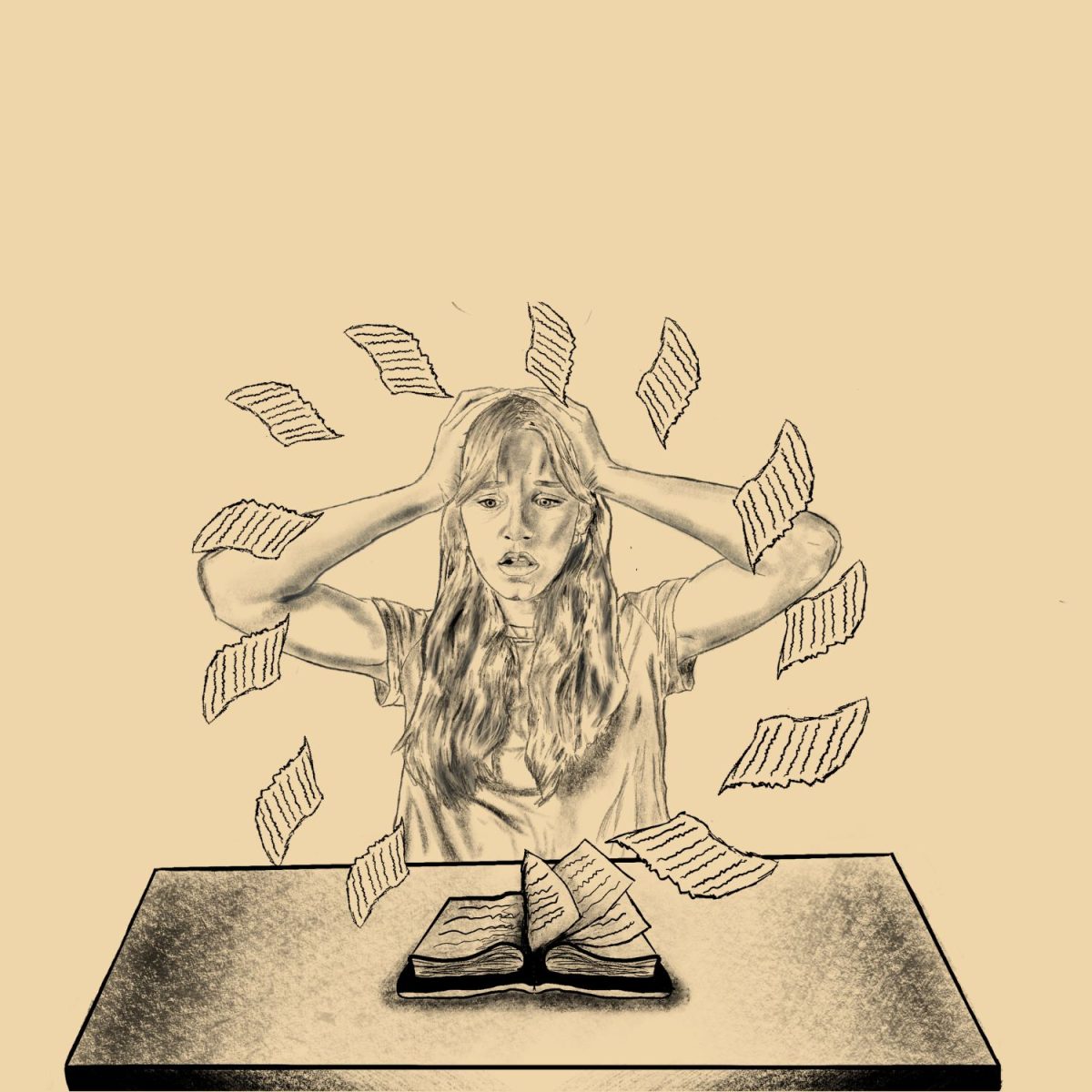

Although each scene is uniquely morbid and mentally difficult to process, Watson’s voice cracks as she explains her initial experiences with the job.

“I saw two suicides on my first day. There was a baby. The children really hit different––it’s really sad, especially when it involves the parent. But I always try to look at it from more of a scientific and medical perspective, so to speak. When I look at a body, I feel the soul is separate.”

This mentality, alongside the support from Chief Medical Examiner Wendolyn Sneed and her team whom Watson describes as “as incredibly dedicated and passionate individuals,” helps her deal with the emotional toll that often comes with a job at the Medical Examiner Office.

Watson’s colleague and 2020 Suncoast High School graduate, Inayat Sood, described her as “very hard working [and] motivated.”

“She knows she wants to go into med school. And she’s only in high school,” Sood said.

With a gaze towards the future, this summer job she originally picked up from mere interest has turned into a serious passion––and a viable career choice––for Watson. “I didn’t realize that this is something I might want to do,” she said, in reference to herself before coming to the Medical Examiner Office.

Curiously enough, Watson’s current pursuits as a Dreyfoos vocal senior are rather unrelated to her aspiring interests. Inevitably, midway through the interview, I hesitate on asking a question that could procure an ingenuine response.

“Do you find any correlation between singing and your job?”

Watson cannot contain her laughter.

“No.” (More laughter.) “Honestly, no.”

Although singing itself doesn’t correlate to her skills used in the job, Watson does find herself at home because of her exposure—albeit unexpected—to music in the workplace.

“When you have to deal with such an emotionally taxing job like [Forensic Pathologists,] do you have to find ways to bring yourself up. They listen to music in the autopsy suites. When I went in [the Morgue], I was like, ‘You guys listen to music while you’re doing this?’,” Watson remarks in retrospect.

And the surprise didn’t stop with the music as it did with what the medical examinets would do while listening to it (Which is to say, Watson received the chance to shadow a medical examiner during an autopsy. For many medical students, this is a once-in-a-lifetime type deal.)

“It’s really weird seeing someone that was walking 48 hours ago being cut open,” she says in awe. “It’s crazy seeing what’s inside of you. Even like, the skin. I’m like, ‘how is that? That’s me.’”

After the interview concludes, Watson gives me a tour of the conference room. She laughs at Phil the Dummy, pulling books off the shelves to show the camera before returning to work. Although “a summer job in the alternate universe of integral operations at Palm Beach County’s Medical Examiner Office” is a bit lengthy of a job description, it is a cool one. And if she doesn’t have time to say that, Watson can always say she touches dead bodies, and laugh.