I cross his street on my morning bike rides. I’ve eaten at the same restaurants as he has. I’m friends with girls from the schools he’s scouted at.

So it’s not weird that my best friend chronicles a visit to this guy’s house on Snapchat, or that my track teammates dance in front of the compound on TikTok. It’s like, mutual friends.

And this definitely wouldn’t be weird if the prime teen hangout spot in question was a beach house or a coastal cafe. But it definitely would be weird if it’s the addy of infamous sex trafficking ring leader Jeffrey Epstein’s Palm Beach Mansion. Right?

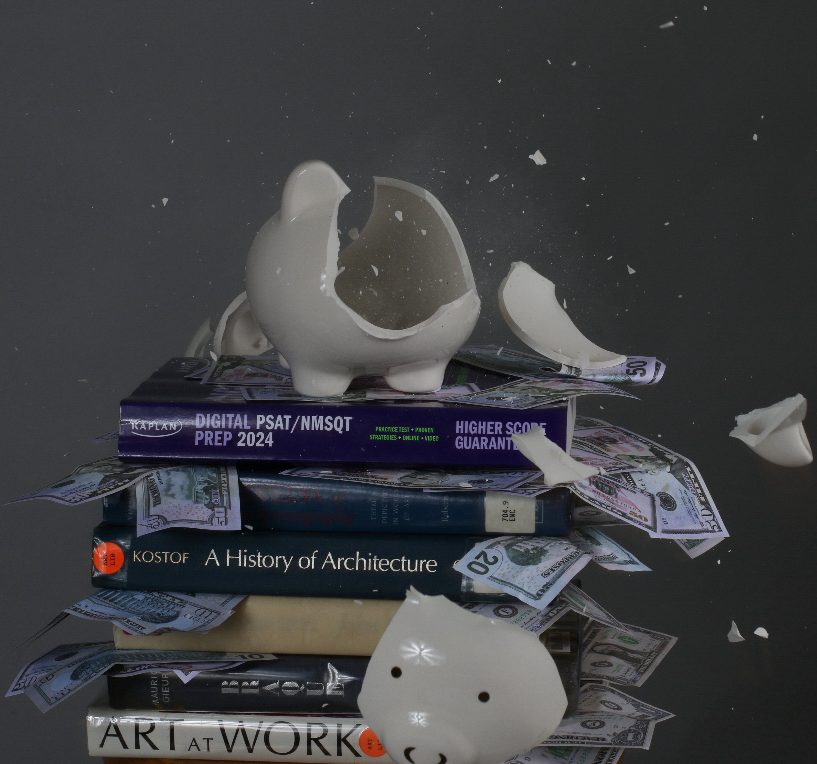

With the arrival of Netflix’s docuseries “Jeffrey Epstein: Filthy Rich,” hordes of sixteen-year-olds have started fangirling over a serial abuser and his housing assets around the country. But in light of twerking on his front door gate, one thing is clear: America has a true crime fetish. And it’s complicated.

Based upon real crimes committed by real people, the true crime genre likes to “dip a pen in gore,” as described by the New York Times in 1987. It “make[s] sense of human brutality, and the public’s feverish interest in real-life murder mysteries” — which is, in essence, the issue with consuming the genre.

Netflix’s 2019 film, “Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile,” explains the story of serial killer Ted Bundy through 2000’s heartthrob actor Zac Efron. Centering on his love story and the ways in which he used his looks to lure in victims, MTV notes that “Much of the criticism centered on the ways [“Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile”] seemed to glorify or humanize Bundy.”

Consequently, over 14 million tags of #tedbundy ran rampant on TikTok. Many of the users impersonate him in order to garner views and followers. And while, yes, the film does acknowledge that his murders were morally wrong, it has opened a gateway for teenagers to the topic of true crime. Experts working with MTV news worried “these cautionary tales are sending mixed messages about infamy and culpability” to young audiences.

And with TikTok cementing itself as a haven and breeding ground for true crime-inspired content, users crushed on a Connecticut murderer, Peter Manfredonia, only several months ago amidst quarantine. On his Instagram, one user went as far as commenting, “you killed it in this pic, kill me next” on his account.

Never mind the obvious risks involved with contacting a murderer (who was, at the time, on the loose,) the bigger question still stands: If we had not been exposed to true crime as casual, Friday night entertainment, would we be fearless in the face of a killer?

The answer is no, because we would not have allowed ourselves to sympathize with cold-blooded criminals.

NPR points out that this sympathy often engenders curiosity within us, and that those with the “capacity for violence” counteract our lack of it. And yes, “lik[ing] creepy stories because something creepy [is] in us” is true. But this constant exposure to evil people that we insist are ‘not that evil’ cracks the soft spots of our hearts, and allows their actions to enter.

Admittedly, I am a big fan of true crime content. It’s often portrayed in an interesting way — for many, it’s the comfort food of film. When done right (or really, done wrong), the people in the dangerous situations become characters whom we emulate emotions for. And how can we say no to true crime, when titles like “Cold Case Files, Don’t F**k With Cats” and “I am a Killer” are among Netflix’s most popular in the genre?

It’s not to say that there aren’t portrayals of true crime done in a morally sound fashion. The YouTube series “True Crime Daily” conducts investigations of true crime mysteries and cases through a journalistic lens. The focus is not to entertain audiences, but to inform them, and that is where a solution to stop murder media consumption lies. The film “Lost Girls” takes into account the real-life story of murdered sex workers in Long Island. Instead of focusing on the killer, the movie centers around mother Mari Gilbert who constructs a community based around the victims’ families. The reason “Lost Girls” is such a success is the “portray[al of] sex workers as three-dimensional people,” according to Time, instead of the criminals as such rounded individuals themselves.

Yet, we must recognize that most often the obsession is not harmless for the victims of the crimes. Save for fleeting moments of representation, most aren’t given a lasting platform. If they are, it often comes in the package of a minute interview window. “Jeffrey Epstein: Filthy Rich” does center around these victims’ stories, but it also centers around the fashions in which Epstein manipulated them, abused them, and indulged in his crimes. In true crime media, the criminal is the star. For me, it is the main reason I am so disturbed my friend’s actions: How can we cede our platforms to criminals? How can we engage with their lives, if on screen or in real life? And most importantly: How can we excuse what they did?

So no, I’m not going to Jeffrey Epstein’s house. I will not post about him, nor will I finish the docuseries. Without the luck of timing, my friends and I could have very easily found ourselves in that house — and we wouldn’t exactly be taking selfies.