Sitting criss-cross applesauce on the purple row of a shaggy, rainbow-colored rug, I listened as my kindergarten teacher flipped through the crinkled pages of “The Magic Treehouse: Dinosaurs Before Dark” by Mary Pope Osborne. With each word she read, a new world opened up to me, a place where I could escape reality and lose myself in adventures beyond everyday life. As I grew, so did the presence of books in my language arts education. I transitioned from book reports about Melody from “Out of My Mind,” to complaining about the ending of “The Giver” with my friends, to protesting Johnny’s death in “The Outsiders.”

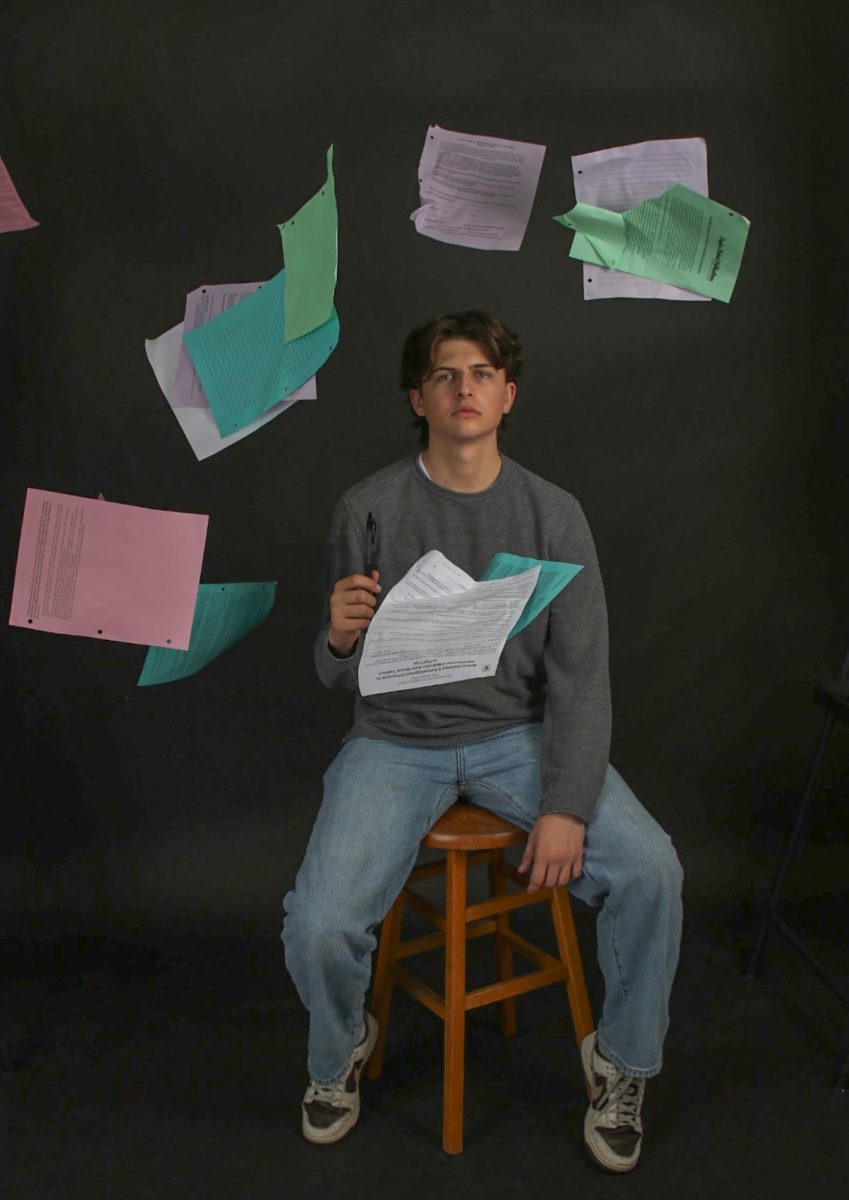

But, as I’ve entered high school, the books that used to be the foundation of my English classes have slowly begun to disappear. I went from reading a book every day in elementary school to only reading one in my freshman year. Over the past few years, high school curriculums have shifted to focus on preparing for standardized tests, simultaneously pushing books further and further into the background of education. In turn, this loss closes the gateway to imagination.

The fact of the matter is that students aren’t reading books anymore. Instead of full-length books, educators have begun to teach primarily using excerpts or shorter passages. In a survey conducted by The Muse, 41.7% of the student body was assigned no books this year in their English classes, with 16.4% saying they had not read a full book since the beginning of the year. These changes are not beneficial for students. In fact, they have a detrimental impact on their literacy.

All over the nation, student literacy, or “the ability to use printed and written information to function in society,” as defined by the National Center for Education Statistics, has been, regrettably, dropping rapidly from year to year.

According to the Nation’s Report Card, a government site that provides information about student achievement in the United States, the average scores on the literacy section of the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) exam have declined by four points in the 2022-2023 school year, shifting the national average score of 260 to 256 out of 500 — a continuation of a downward trend. In 2020, the average score was 260, and in 2012, it was 263. With each new generation of students, reading comprehension, vocabulary, and critical thinking skills are declining.

For instance, it may prevent people from getting certain jobs, communicating with others, and gaining important information about the world around them. Both nonfiction and fiction books teach students valuable information. Students who read are able to learn about people who are different from them through books, allowing them to grow their empathy and relate to characters who experience struggles similar to theirs.

Yet the school system has fallen short. Even after years of schooling, many students graduate without the ability to read at the level expected of their age cohort.

According to the National Literacy Institute, “approximately 40 percent of students across the nation cannot read at a basic level.” This significantly limits their future potential, and books are the solution. In order to get back on the same page, we need to reimplement reading full books back into English class curriculums.

Although it seems like the shift away from books is due to teacher preferences, they are actually not behind this change. The actual reason arises from years of pressures stemming from statewide standards. As curriculum guidelines have gotten stricter, many educators no longer have the time to teach their students using books. In a survey by The Muse, out of the English teachers at the school, 50% said they do not give assignments using full books for their students due to restraints from the curriculum.

One example of this was the implementation of Florida’s Benchmarks for Excellent Student Thinking (B.E.S.T) standards for English Language Arts that began in 2022. With this change, teachers had to relearn lessons they taught their students, often having to adjust major parts of the lesson plans and curriculums with which they were familiar. When teachers are pressured to quickly conform to new standards in our education system like this, they have to make enough time during their classes to ensure that their students receive all the information they need, leaving little room for books, and in turn, hindering those students from being able to achieve their full potential.

Focusing on test preparation does the same. Standardized tests evaluate student performance based on their comprehension of small excerpts — not books. To help their students prepare, teachers have begun to lean more towards shorter passages, mirroring these tests and replacing the use of books.

Although this is understandable, problems arise when students are prevented from gaining skills that only come from reading full-length books. Paragraphs and excerpts may prioritize quick comprehension and identification skills, but they leave gaps in a student’s learning.

Some include critical thinking and decision making. A person’s ability to evaluate information increases significantly when the text they are reading is lengthy. While shorter passages do hone these skills, developing ideas and conclusions throughout an entire book takes a deeper level of critical thinking. This increases students’ abilities to assess multiple perspectives, gain greater logical reasoning, and problem solve more effectively.

The Harvard Business Review wrote that research suggests that “reading literary works is an effective way to enhance the brain’s ability to keep an open mind while processing information,” which is a necessary skill in decision making. Students with little exposure to full books may eventually find themselves unable to assess important situations or effectively form opinions about the world around them.

Additionally, books offer cultural enrichment. Once, my aunt and I were debating if she should get another dog when she made an offhand comment: “To be or not to be, that is the question.” I later learned this was a reference to Shakespeare’s “Hamlet.” Literary works like those are languages in themselves, uniting people regardless of age, gender, or culture. But just like a language, if no one practices them, they are at risk of disappearing forever.

According to Cambridge Scholars Publishing, “There is a direct association between classical literature and culture and they both align with each other. The culture embraces the beliefs and values of society and the literature, on the contrary, conveys them in different literary shapes.” Books and other literary works are windows into the past, allowing people to learn about human nature and society in previous years. They hold cultural values that, for many, have faded into the past and can only be found within their pages, making it vital to keep these works alive.

Will they understand why we say “go down the rabbit hole” or that someone is “as mad as a hatter” if people no longer read “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”? Will they understand when someone says, “wherefore art thou,” they are alluding to “Romeo and Juliet,” or will they think of Sabrina Carpenter’s “Bed Chem”?

Reading entire books also improves concentration and a person’s attention span, combating the quick bursts of information that are becoming the priority in almost every sector of our lives. Even when students do read, they may be unable to remember what they read because their minds are not accustomed to processing the information. We have such short attention spans that when we research something, an Artificial Intelligence (AI) blurb pops up immediately with a short summary of the topic. In the entertainment space, minute-long videos are more popular than ever.

Being able to immerse yourself in a single task for extended periods of time is a skill our generation lacks. If you can’t focus, you can’t give your undivided attention to something, impairing your ability to fully understand what you are doing. Unfortunately, our attention spans are rapidly declining, depriving us of the ability to focus for extended periods of time. If I’m not able to get through a TikTok storytime without a clip of someone playing “Subway Surfers” at 2x speed next to it, how will I ever have the patience to read my textbooks in college, complete my taxes correctly, or even just hold a long conversation? Soon, we may lose the ability to concentrate altogether.

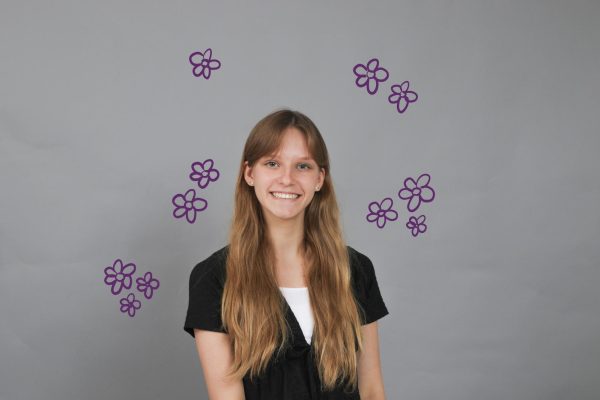

I often get caught up in the tendency to rush or multi-task everything I do. I complete my math homework while listening to a podcast, and I eat breakfast while watching a YouTube video. But every night before I go to bed, I make sure I read a book for at least 15 minutes. It’s the only time in my day where I am truly able to let the rest of the world take a backseat and I can stay centered in the moment, doing only one thing, thinking about only one thing. This time has allowed me to regain the ability to concentrate on my tasks, not only reading, but anything — both academically and non-academically. Reading allows us to bring back focus into our day in an age where it’s slipping away.

However, not everyone has time to read like I do. In a survey by The Muse, out of students who have read three or fewer books this school year, 28.1% said the reason is due to not being assigned books by their teachers while 60% attributed it to having a lack of free time, which is why it is so imperative that we give students the opportunity to read in their English classes.

In an article by The Atlantic, Columbia University professor Nicholas Dames found that, over the past decade, his students have become “overwhelmed” by the idea of reading for his class. “College kids have never read everything they’re assigned, of course, but this feels different. Dames’s students now seem bewildered by the thought of finishing multiple books a semester,” stated the article, titled “The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books.” “Many students no longer arrive at college — even at highly selective, elite colleges — prepared to read books.”

Solving the problem of dwindling student literacy rates is not going to happen right away. Just like how the shift away from books has been gradual, going back to where we used to be will be gradual as well. However, I believe the key to a resolution is right where I, and millions of other kids, fell in love with reading for the first time — the classroom. By implementing more full-length reading time into the curriculum, students can develop their minds and grow their reading skills, promoting literacy on campus and throughout the nation.

If teachers are unable to squeeze books into their curriculum, literacy can be supplemented in other ways. In many of our English classes, we spend 15 minutes doing vocabulary practice, so why not add in 15 minutes of free reading time to help the students on our campus, just as 15 minutes of reading has helped me? If teachers are unable to give up 30 minutes of non-instructional time during a class period, they could instead trade off each week, alternating between vocabulary practice and reading.

Adding books back into school curriculums may be a jarring shift for students, so these 15 minutes will allow them to transition smoothly into reading, building a foundation for the future. When students are able to choose what they read, they are able to reap the benefits offered by reading while also having fun, encouraging them to read more on their own.

A few courses have literary works built into their curriculums. For example, students in Advanced Placement (AP) Literature often read “Jane Eyre” or “Hamlet” in their classes. Courses like these require students to read novels or plays to prepare for standardized tests, which enables students to grow their reading skills and their knowledge of historical works. If more courses used this approach, more students would be able to benefit in the same way.

If we want future generations to have the opportunity to succeed, it is imperative that we allow them the opportunity to read.

*The data included was gathered from a casual survey given by The Muse through Google Form via English classes from Jan. 28 to Jan. 31, 2023 to 829 students.

mia • Apr 8, 2025 at 10:34 pm

absolutely cooked with this article and i completely agree, the final line btw omg i had to read it again just to fully take in the perfectness and cleverness (not sure those are words but you know 🤷♀️)

Mike Kirby • Mar 21, 2025 at 9:14 pm

This article was very well done.I agree with the author. Not only was it expressed well it was flawless in execution. I did not find a single misspelled word or other grammar error. The artist portrait is a nice complement to the work. Thank you for sharing it with me!