Kooks can’t surf. Pogues live for it. But Pogues don’t golf. Or race fancy speedboats. Or belong to country clubs. That’s Kook turf. Kooks only wear fresh pressed polos, while the Pogues deck out in bandanas and clothes bearing the rips they sustained during police chases.

If you’ve logged onto social media in the past month, chances are you’ve heard the name “Outer Banks,” a new Netflix show that tells the story of “two tribes [on] one island,” as main character John Booker Routledge (John B) said. Although it can be categorized as a predictable adventure drama, this show taps into something more profound: The emotional struggles of cliques and the consequences of betraying this loyalty.

The plot of “Outer Banks” follows John B, and his Pogue friends Kiara, Pope, and JJ, as they delve into the mystery of the Royal Merchant, a gold-laden ship that had been lost at sea. The Royal Merchant was a real ship that capsized in 1641, carrying a modern value of over $1.5 billion in precious metals. Although fictionalized on screen, the real Royal Merchant still hasn’t been found.

SPOILER ALERT: There are spoilers ahead in this review. If you wish to avoid spoilers or haven’t yet seen the series, I suggest you refrain from reading on.

While the mystery seems to become more troublesome than reward-reaping, they find unlikely allies along the way (like Sarah Cameron, a total Kook-turned-Pogue who becomes John B’s love interest). The show also focuses on the characters’ personal struggles: abuse from JJ’s father, drug addiction with Sarah Cameron’s brother, and John B’s imminent foster care placement. These heart wrenching moments are reminders that the gold isn’t with the Pogues, and although it might be soon, real life continues.

The show, in many ways, is a triumph. Aside from highlighting tense social relations on the basis of affluence, it also explores the idea of living for the present. The teenagers in the show are seen on adventurous excursions and standing up for themselves without the presence of adults or even phones. The performances from Chase Stokes (John B) and Madelyn Cline (Sarah Cameron) are to be commended for their strong chemistry, carried on even when “nothing in their characters’ relationship makes any sense in the event that the season takes place over a week”, rather than the illusion of several months.

Most notably, the idea of feuding between Pogues and Kooks can be applied to virtually any high school. “Outer Banks” correctly mimics the cliché lunch scene at high school, where varying interests and disparate social hierarchies make cafeterias near war-zones. The buzz around this drama is due to the “pragmatic juxtaposition of sociopolitical disparity” showcased not by adults, but rather, by kids. The differing reactions to conflict and jealousy are arguably challenges that most any teenager faces off screen (other than the race for lost treasure part.) Given this potent relevance, it’s no surprise that the show hit number one on US Netflix by its third week. If you’re interested in finding out whether you’re a Kook or a Pogue, take this quiz made by the Muse.

The ending of the first season is justly heartbreaking. Both the Pogues and the Kooks are left to grieve the apparent deaths of John B and Sarah Cameron, where possibilities of the cliques joining forces is pondered. However, the most important plot questions are blatantly surface-level: Where was the gold shipped in a shocking twist? The Bahamas. And who’s going there, perfectly alive on a cargo ship? John B and Sarah Cameron.

Essentially, these questions and the plot get very dramatic. Sometimes, viewers are left wondering whether some of the events are even possible to achieve in real life. How do John B and Sarah Cameron manage to escape hoards of police, both in the water and on land? And how did they survive such a powerful storm? In some parts, the script “falls short of poetry,” with John B’s introductory voice-over stating the obvious, rather than information unbeknownst to viewers within the first ten minutes of the episode.

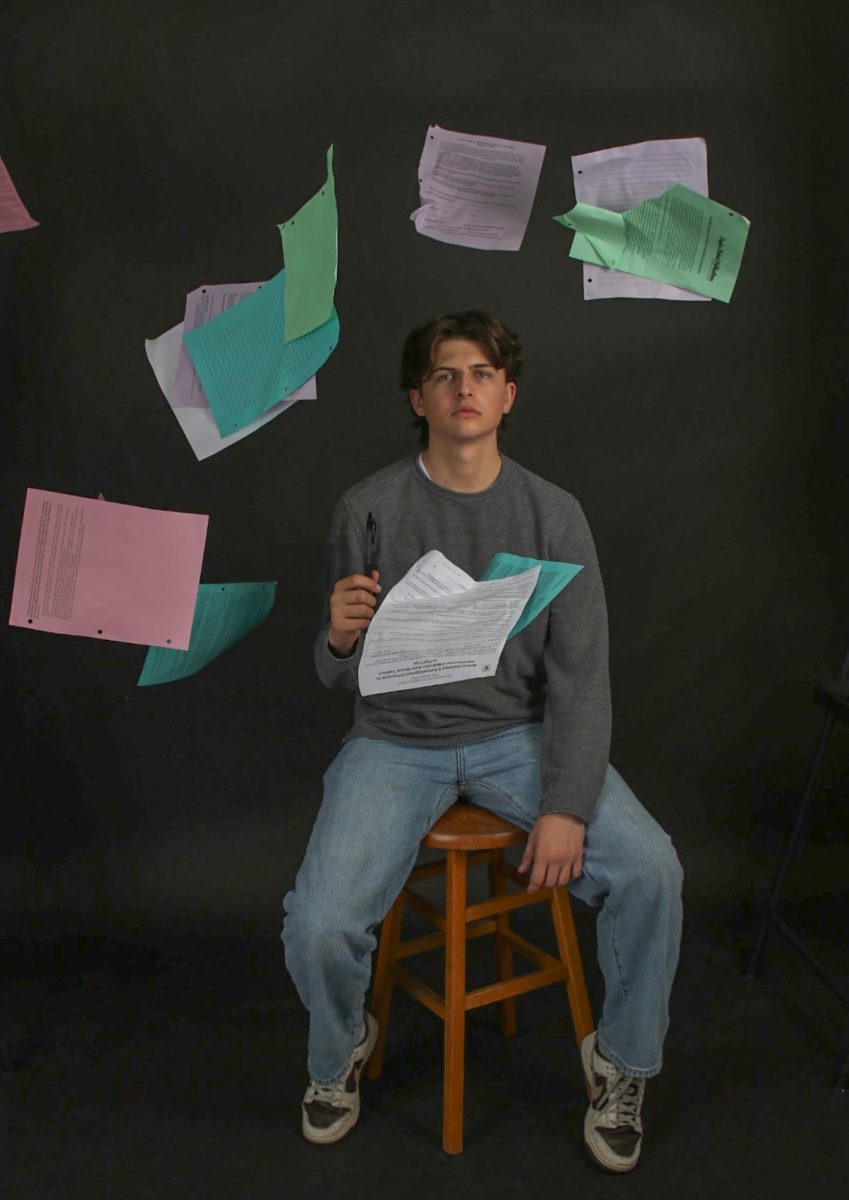

An additional downfall is that in real life, the actors are much older than 16, with Chase Stokes being 27 years old, and the youngest of the seemingly 16-year-olds being 21. It sets an unrealistic expectation for looks and maturity when real 16-year-olds compare themselves to what they see on screen. The toned and muscular grown adults leave little room for the inclusivity of other body types. Evidence is in the reviews for “Outerbanks,” dominantly headlining with “Teens” and “Shirtless,” rather than viable content of the show. The TomatoMeter gives “Outer Banks” a 70 percent approval rating due to some of these flaws.

Nonetheless, “Outer Banks” reminds us of the summer ahead amidst quarantine. After watching the ten episode drama, it’s difficult not to want a friend group as tight knit as the Pogues. The exploring of a deserted church just to ring its bells seems like a perfect way to enjoy June, July, and August right where we are. And, worst case scenario, we’ll live out our wild summer dreams through the Pogues and their crazy mystery, all while we wait for Season 2.

![[BRIEF] The Muse recognized as NSPA Online Pacemaker Finalist](https://www.themuseatdreyfoos.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/IMG_2942.jpeg)