It’s that simple form of gratification: Tossing a plastic bottle into the blue bin makes people feel good for the rest of their day.

It’s too good to be true.

Because what these do-gooders fail to realize is that recycled bottles don’t travel away to a fantasy land to be transformed into new, sparkly products when they are tossed into the blue bin. The gritty reality is that they’re essentially tossing that bottle into a giant plastic heap in South America. Recycling no longer solves our problems—it causes them.

From the Silk Road to Plastic Express

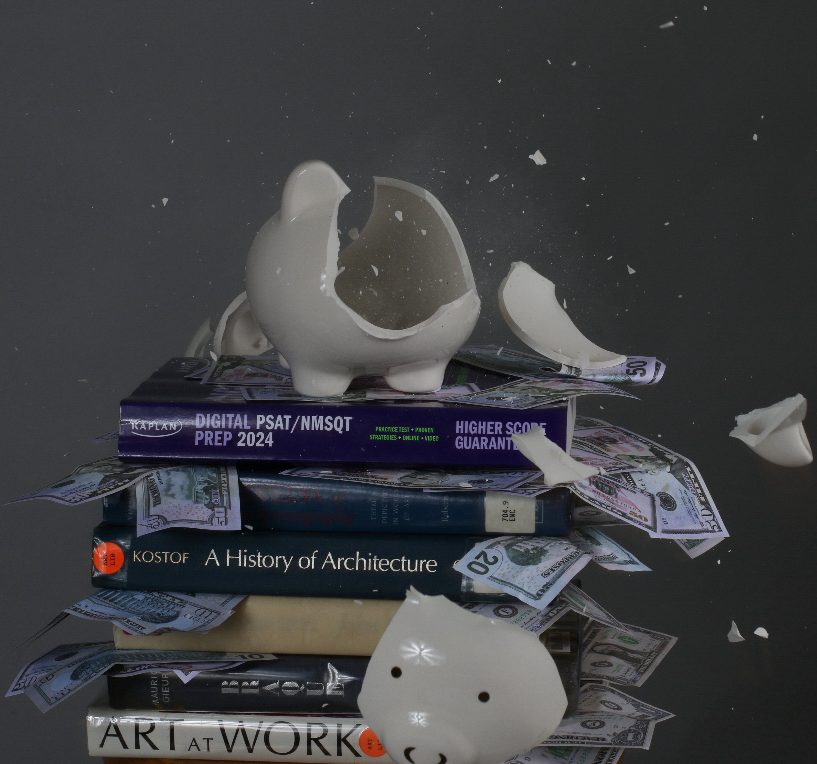

Until recently, the vast majority of the United States’ recycling and other waste went to China to be transformed into new goods and products. In fact, 7 million tons of plastic traveled to businesses in China annually, accumulating to 70 percent of global plastic waste. China has taken nearly half of the United States’ recyclable material because we don’t have the infrastructure to process it.

That all changed with China’s National Sword policy, put into effect on Jan. 1, 2018. The law banned 24 types of foreign recyclable waste and ended the collection of any other materials that were unable to meet a contamination rate of 0.5 percent or less, which, by many regards, is impossible, especially for municipalities (Palm Beach County’s contamination rate is 8-9 percent, which is considered very low). China justified the sudden change by pointing to the fact that materials imported into the country were heavily contaminated and caused environmental degradation, as they couldn’t be recycled and were just directed to landfills. A year after implementing the policy, plastic exports to China drastically dropped by 99 percent.

Out of sight, out of mind…

How has Palm Beach County handled this problem? According to the local Solid Waste Authority, it has found success in exporting materials to other markets. The problem is that these are usually developing countries such as Vietnam and those in Latin America. Just like the United States, they don’t have the infrastructure to deal with the huge influx. As a result, in these nations, 15-foot piles of plastic waste sit in the sun for months, polluting communities and their water sources.

It is the ultimate form of neo-imperialism: Quite literally, America is dumping its trash onto poorer countries for them sort through and try to make some use of it.

Palm Beach County’s waste may also find itself in waste-to-energy plants, where the recyclable material is burned and churns out “renewable energy.” But, these plants cause more air pollution than natural gas plants and pose serious health hazards.

And this is one of the good stories—around the country, local governments use single-stream programs and don’t have access to these “innovative” waste-to-energy plants, meaning their landfills are becoming overwhelmed.

But, the problem with recycling doesn’t stop there. Even if there were a magical recycling plant far, far away in a fairy tale land, the issue of contamination persists. From the recycling of dirty materials to non-recyclables, such as old hoses, people with good intentions continue to contaminate the system’s flow. For example, in New York, only 16.5 percent of the collected plastic was considered recyclable.

Fixing the problem

The mantra, “reduce, reuse, recycle,” often gets oversimplified: Just throw the plastic thingy into the blue bin—it’s as simple as that. Right? However, people fail to recognize the most important parts—reduce and reuse. Recycling needs to be our last resort. Throwing plastic bottles into the recycling container is far different from having a reusable water bottle, and the same goes for reusable lunch bags, straws, etc.

The average lifespan of a grocery bag is 12 minutes, but it hangs around for 500 years. Single-use plastics have filled the world around us, tainting the very air we breathe. The problem is that using these plastics in any situation is a rash mistreatment of the commodities consumers use. Yes, it is convenient, but it happens at the expense of the Earth.

This is not to say that recycling shouldn’t be practiced ever. After all, it’s far preferable to have the few materials that are actually recyclable recycled than being shoved into landfills, but it needs to be acknowledged that the system is far from perfect. Recycling should not be a placebo effect placating the masses into a false sense of environmental friendliness. So as we enter a new era of prioritizing Earth over cheap yet destructive plastic, the question we are asking ourselves daily shouldn’t be “Is this recyclable?” Instead, let’s ask, “Why have that much waste anyway?”

![[BRIEF] Class of 2024 Top 20](https://www.themuseatdreyfoos.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/breaking-news-1200x927.png)